In Memoriam: Jerome A. Cohen

From News Media

Wall Street Journal: “Jerome Cohen, the First American to Practice Law in China, Dies at 95,” Sept. 23, 2025.

South China Morning Post: “Jerome Cohen, respected China law expert – and regular critic – dies at 95,” Sept. 24, 2025.

Law.com: “Jerome Cohen, The Original 'China Hand', Dies At 95,” Sept. 24, 2025

BBC Chinese service: “孔杰荣逝世:中国法律研究先驱的传奇人生,” Sept. 26, 2025.

New York Times: “Jerome Cohen, Lawyer Who Plumbed Chinese Legal System, Dies at 95,” Sept. 27, 2025.

The Economist: “China’s most optimistic critic,” Sept. 29, 2025.

Other Institutions and Government

U.S.-Asia Law Institute: “Remembering Jerome A. Cohen: Field Builder, Rights Advocate, and Mentor,” Sept. 23, 2025

East Asian Legal Studies at Harvard University Law School: “Tribute To Professor Jerome A. Cohen (1930-2025),” Sept.23, 2025

NYU School of Law: “In memoriam: Jerome A. Cohen (1930-2025),” Sept.24, 2025

Institutum Iurisprudentiae Academia Sinica: “In Memory of Professor Jerome A. Cohen, Emeritus Professor of Law at New York University School of Law,” Sept.24, 2025

Consulate General of Japan in New York: statement on Facebook, statement on Instagram, statement on X., Sept. 30, 2025

Council on Foreign Relations: “Jerome A. Cohen: Legal Pioneer, China Expert, Mentor, and Friend,” Oct. 1, 2025

Personal Tributes

呂秀蓮:敬悼 孔傑榮教授, Sept.24, 2025

許章潤:精神家族一代師表——思祭孔傑榮先輩:許章潤誄孔公 (English translation by G.R. Barmé), Sept.25, 2025

张千帆:中国法治的“不老松”——追忆孔杰荣教授, Sept.24, 2025. Click here for the English translation by Pekingnology, Sept.28, 2025

-

In Loving Memory of Professor Jerome Alan Cohen

Yun-chien Chang (Jack G. Clarke Professor of East Asian Law, Cornell Law School; LL.M 06’; J.S.D. 09’)

It is still difficult to believe that Jerry has left us.

I first met Jerry in his office in May 2009. In just a few days, I would return to Taiwan to hopefully begin an academic career. Jerry was already 75 years old at the time. Though he walked slowly, his voice remained resonant, full of humor and warmth, generously sharing his life’s wisdom with a junior colleague nearly half a century younger.

Little did I know that over the next decade, I would have the privilege of encountering Jerry in various corners of the world. Once, I attended a panel discussion he was moderating. I had expected the typical format—a moderator who simply keeps time and ensures speakers take turns. But Jerry elevated the role of “moderator” to a level that was surely unprecedented. He would interject at just the right moment with sharp, insightful commentary. He asked questions that drew out the best in each speaker and called on participants with an uncanny intuition for their perspectives and areas of expertise. It was clear that he knew everyone in the room—who they were, what they thought, and how to bring them into the conversation at just the right moment. His ability to orchestrate such a high-efficiency, intellectually rich exchange left me speechless. After the session, I told him how amazed I was. He smiled and replied in Mandarin: “我是老狐狸了” (“I’m an old fox”). Some of the tributes written about him since his passing have mentioned how adept he was at using Chinese idioms—this was one such moment I will never forget.

Throughout the 2010s, whenever I passed through New York for conferences, Jerry never hesitated to invite me to give a lunch talk at NYU Law, my Alma mater. I had imagined a typical format where I would present a coherent academic narrative and field a few scattered questions from the audience. But of course, that wasn’t Jerry’s style. He said, “Let me interview you.” I asked how I should prepare. He said, “There is no need for you to prepare. Your whole life is your preparation.” For a young scholar, that was both thrilling and terrifying. I certainly hadn’t spent my whole life preparing for a lunch talk! But the session unfolded under Jerry’s wise, witty, and perfectly paced questions—and I found myself responding more freely and insightfully than I could have imagined. A few years later, we repeated the same format at again. This time, Jerry asked entirely different questions, drawing out a different set of reflections—almost as if this man, then in his late 80s, had remembered every word I had spoken years earlier.

In the spring of 2019, I returned to NYU Law School as a Global Professor. Jerry, then 89 and not yet retired, invited my wife, son, and me to dinner on our second night in New York. The photo we took that evening captures a moment I will always treasure. After dinner, he and his beloved wife Joan graciously welcomed us into their home—a home that felt more like a private museum. The way he had arranged the artwork, and the stories he told about each piece, left us spellbound. My favorite museum in the UK is the Sir John Soane Museum, a compact but remarkable space near the British Museum—created by a man of many talents who turned his home into a personal museum and opened it to the public after his death. Visiting Jerry’s home felt like stepping into the Soane Museum—with the rare privilege of having the master himself as our guide.

Now, that voice is gone.

I’ve been reflecting: if someone like me, who came into Jerry’s life relatively late, received so much of his generosity, care, and encouragement, then how much more joy and love must he have spread to others—both the great figures of his generation and younger colleagues like myself? As I read through the tributes on news sites, in email threads, and across social media, I find story after story, each full of warmth and gratitude. I think I now understand the answer.

Jerry Cohen’s life was a gift to us all.

-

In memory of Jerome A. Cohen (1930-2025): Jerry, as I remember

The passing of Professor Jerry Cohen is a profound loss, not only to the field of Chinese law studies but also to many of us personally. Friends and colleagues have shared numerous tributes, attesting to the significant impact of his life. We remember Jerry—as he preferred to be called—as a community. Now that he has left us, we become the keepers of his memory. And we pass this memory on by telling Jerry’s stories, as he, a storyteller, would have liked us to do.

Working for Jerry at NYU in the previous decade—though he’d always graciously insist it was “working with”—was a great privilege, allowing me to witness an extraordinary man in action. To share those memories, perhaps the Chinese term 喜怒哀樂 (joy, anger, sorrow, and happiness), capturing the most fundamental emotions of life, is a fitting place to begin.

Joy

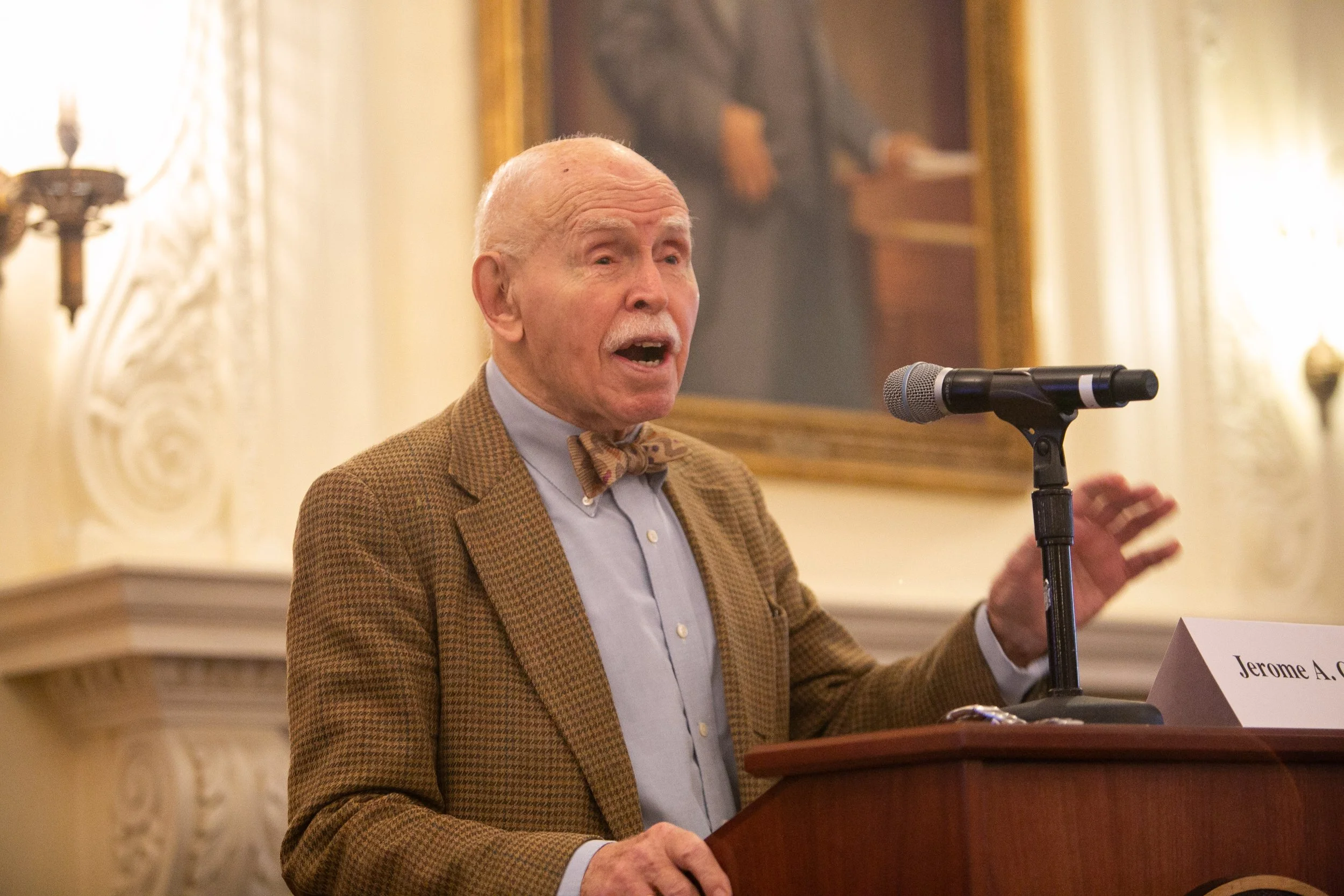

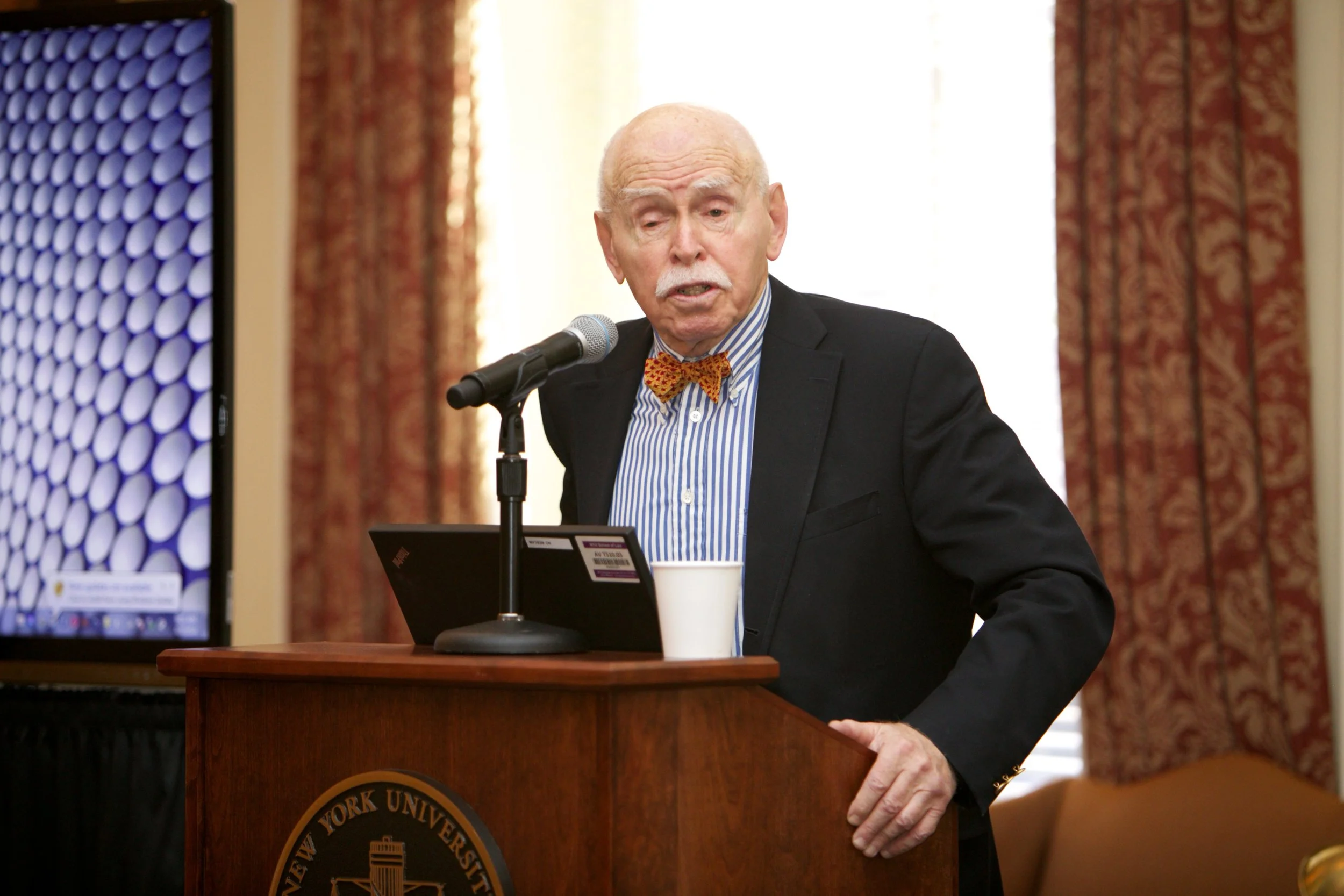

With his signature bow tie and dignified mustache, Jerry appeared serious and even a bit intimidating at first glance, but once conversations started, you knew he was full of joy, had a great sense of humor, often accompanied by a mischievous twinkle in his eyes, and treated those around him with warmth, kindness and humanity. I believe his secret life recipe was a genuine interest in everyone he met.

Jerry, for example, liked “interrogating”—in his own words—guest speakers at the weekly lunch meetings he hosted at NYU’s US-Asia Law Institute, one of his favorite activities. During those conversations, he would get personal, asking where they were born, what it was like growing up there, why they studied law or China (or both), and what motivated them to pursue their chosen path. Jerry was genuinely curious about the stories of people; each one, he believed, had something unique to tell.

Jerry himself famously loved telling stories (and jokes), and they never failed to fascinate us. It was remarkable how he was able to use a story to illuminate something larger, though he also loved a good story simply for the joy of it. Among his immense repertoire, some were all-time favorites, inevitably summoned more than once or twice. As Jerry knew, we junior colleagues even schemed to create a code system where each joke had a number, so he only needed to call out the number, and we could all laugh without missing a beat!

Anger

I rarely saw Jerry angered, but when he was, he was fierce.

Whenever Jerry traveled to China, he always made a point of visiting Chinese human rights lawyers, despite the obstacles. In 2010, Jerry went to see the Shanghai human rights lawyer Zheng Enchong, who had been under house arrest for years (he had tried visiting him previously but was stopped by the police). As Jerry and I approached lawyer Zheng’s apartment, we were, unsurprisingly, blocked by several plainclothes police officers in the courtyard. Jerry kept asking what legal basis they had to prevent us from seeing a supposedly free Chinese citizen. As the argument escalated, Jerry grew increasingly outraged. He did not back down. He was determined to see lawyer Zheng this time. After intense negotiation, we agreed to come back the next day, finally getting to see Zheng and his family. The police likely did not want to contend any longer with Jerry’s wrath.

Sorrow

As Jerry wrote in his memoirs, he was born in 1930 into a middle-class Jewish family in New Jersey. Both his father and mother came from immigrant families from Europe. Jerry lost several relatives in the Holocaust during WWII. Even after the war, Jewish people in America continued to face various forms of discrimination.

In one group meeting where a Chinese anti-discrimination advocate was invited to speak, Jerry introduced the speaker and emphasized the importance of this topic. He began to relate it to his family’s experience. In the middle of a sentence, he suddenly stopped talking, and the room fell silent—for the first time, we saw Jerry cry, overwhelmed by emotion. I often wondered if this personal experience had played a significant role in motivating his work on human rights, rooted in his deep compassion.

Happiness

Nothing brought Jerry more happiness than knowing he helped others. He did this with great satisfaction and a sense of purpose. When Jerry was asked what he was most proud of in his long career, instead of mentioning his groundbreaking scholarship in Chinese law or his pioneering role as the first foreign practicing lawyer in China, he spoke about helping people and, at critical moments in history, intervening to save some of them from dire circumstances.

Many colleagues have recounted how Jerry literally changed their lives (mine included). He would bring people to the field, make introductions for them, find scholarships, provide references, and help them secure positions where they could contribute. He saw great potential in people, even for those of us who could not see it ourselves.

Jerry’s happiness came from the community he built, a community inspired and uplifted by his supportive hand. He liked the phrase, “He who acts through another, acts himself.” This is very true. As Don Clarke said, Jerry “lives on in a very real way in the people and institutions he fostered over the years.”

In one of the early meetings, I asked Jerry what I should do with my life. He said, “Do something that interests you, something you can take responsibility for, and, most importantly, something meaningful.” He led by example—again and again, in countless ways—through his extraordinary life.

-

I first came to know Professor Cohen through his academic works in the mid-1980s when I began my study of Chinese law in Sydney, Australia. It has been a great privilege and honour to know him on a personal level and to maintain contact (though, regrettably, too infrequently) with him since the 1990s. It saddens me deeply that I will never be able to meet him again.

He was not just a great scholar, teacher, and legal practitioner; he has always been an inspiration for all who aspire to be decent persons and who care about justice and human compassion. The passing of this giant is the end of an era, and the world is now much poorer without Jerry.

RIP, Jerry, we will all miss you and remember you!

Jianfu Chen

Honorary Professorial Fellow, University of Melbourne School of Law

Emeritus Professor, La Trobe University

-

As someone who as a young scholar in Hong Kong entered upon human rights advocacy and scholarship in the late 1980s, Jerome Cohen, or Jerry as we all know him, is someone who was always there. He was to us all the "father of China law studies." He was also very much a supporter of Hong Kong. As someone who was busily working on developing the rule of law in China in Deng Xiaoping's reform era, Jerry initially appeared cautiously optimistic about China's commitments to Hong Kong. That optimism would soon fade. I recall some years after the handover, when he was in Hong Kong to speak at the University of Hong Kong, another university in Hong Kong declined to host both Jerry and me, judging our views were too controversial for the times. By those days Jerry was working hard on behalf of human rights defenders in China. When we were declined for that other event we took to a coffee shop to commissorate about our rejection and appreciate that such rejections usually signals you are doing something right..

Jerry was of course not deterred in his advocacy and support for China and Hong Kong. I personally found myself invited several times to speak on Hong Kong and Tibet issues at his US-Asia Law Institute at New York University, where I am still an affiliate scholar. During those visits I was able to spend time with him and Joan at their home on the Upper East Side in New York. He was always so magnanimous in sharing his China law journey, regaling us with stories of the early days, many of which were reflected in the pictures and paintings on his apartment walls. I was struck by his sharp memory of that journey and his informed analysis of current developments. As my daughter, Hana, at 22 had just published a memoir of her growing up during the protests in Hong Kong, I joked with Jerry that he should have started sooner on his own memoir. I am happy to say that he finished that this year and it is well worth reading for anyone who wants to understand the importance of the rule of law: Eastward, Westward, A Life in Law. I last visited Jerry months ago at his old family home on Cape Cod. Even though he was not well, I was again struck by how well read and up to date he was discussing his current concerns about developments in China, seemingly looking past his emerging health challenges. Our loss is also a great loss for China.

-

In Loving Memory of My Mentor, Professor Jerome A. Cohen

On the morning of September 24, I was shocked and deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Professor Jerome A. Cohen. Memories of my time with him flooded back. From 2018 to 2019, with his generous help, I had the privilege of spending a year as a visiting scholar at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute (USALI) of NYU School of Law. During that year, I attended nearly all the lunch dialogues and conferences he hosted and audited his seminar, “Law and Society in East Asia.” Professor Cohen was not only a founding figure in U.S.-China legal exchange and a giant in Chinese law studies, but he was also my mentor and a role model for my generation. From here on, as was his preference, I will call him Jerry.

In early 2018, I had just received a Fulbright grant but was struggling to find a host institution. The first time I contacted Jerry, I ventured to ask if he could help inquire about another research institute on my behalf, and I couldn't help but feel apprehensive. To my surprise, Jerry replied quickly and agreed to help. Later, when he learned that the institution was overloaded, he immediately asked if I would be interested in applying to the USALI. I felt deeply honored and, with the deadline from my grant sponsor approaching, I gladly accepted. However, the application period for visiting scholars at the Institute had already closed. In the end, it was only through the joint efforts of Jerry and the then-Executive Director, Ira Belkin, that I successfully received an invitation. I have always been deeply grateful for this, but I was also wondered: why would Jerry go to such lengths to help a young scholar he had never met? It wasn't until I arrived at NYU and witnessed how he interacted with students and junior scholars that I understood. This was simply who Jerry was: he treated everyone as an equal, regardless of age or status, always with sincerity, warmth, and a readiness to show care.

Listening to Jerry's lectures at NYU was a pure pleasure. His main topic was the history of China's legal system, with a focus on the period after the Reform and Opening-Up. He would always begin his talks wearing an elegant bow tie, his magnetic voice—deep yet firm—speaking eloquently, as if recounting treasures from memory. What I admired most was that, at the age of 88, he never relied on notes, let alone a PowerPoint. He could speak for 40 minutes, his thoughts flowing clearly and logically, without even needing a sip of water. After a few classes, I realized that Jerry seldom quoted classical texts or lectured on grand theories. He was always presenting facts and telling stories, and the most captivating of all were the ones he had been there—they were truly histories. I still vividly remember certain moments. Watching history—his story—come to life and unfold before my very eyes in the classroom was a mind-blowing experience that is hard to put into words. Such, perhaps, was Jerry's philosophy of scholarship and teaching: an empirical philosophy, seemingly simple yet deeply profound. The most reliable and ultimate form of experience was his own. This was not the superficial "empiricism" we often criticize, but rather a lifetime of wisdom and historical insight, refined through reflection, contemplation, and verification.

This philosophy also permeated the "Asia Law Weekly Lunch Dialogue" he hosted every Monday. Each dialogue was a feast. First, it was a literal feast, as Jerry always insisted on ordering Chinese takeout for everyone. In Manhattan, this was no small expense. I later learned that his persistence was not due to an ample budget or a gimmick to attract attendees, but rather stemmed from a deep respect for Chinese culture and a wish for American students to better taste its richness. Of course, it was also an intellectual feast. Compared to his seminar, the atmosphere here was more relaxed and free-flowing. Jerry’s guests came from all walks of life, not just academia. It was an open conversation guided by Jerry rather than one-way presentations. He would always begin by asking about the guest's life or scholarly journey, then delve deeper, layer by layer. Following his line of thought, a panorama of China as seen through the world's eyes would unfold. The audience could not only empathize with the guests and their connections to Chinese law but could also feel Jerry's true character—his sincere and profound love for Chinese culture and the development of China’s rule of law.

As my visit came to an end in 2019, I had hoped to have a good talk with Jerry about my year's experiences, but he happened to be away on vacation. At the time, I assumed I would be back in New York soon. Little did I know that with the unpredictable turns of the whole world, it would be our final farewell. To me, Jerry was the epitome of an academic mentor, a university educator, and a scholar of Chinese law.

Perhaps the best way to remember Jerry is to be like him: to treat students seeking help with the same warmth and enthusiasm; to seek the true essence of law through personal experience; and to always hold a deep love and anticipation for the progress and development of the rule of law in China.

Sun Ping

Associate Research Professor, School of Law, East China University of Political Science and Law

Fulbright Visiting Scholar, U.S.-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law (2018-2019)

深切缅怀恩师柯恩(Jerome A. Cohen)教授

9月24日晨,惊悉柯恩(Jerome A. Cohen)教授溘然长逝,不胜悲痛。与先生交往的点点滴滴瞬间涌上心头,思绪万千。2018至2019年,我有幸在先生的帮助下,于纽约大学法学院美亚法研究所(U.S.-Asia Law Institute)访学一年。期间,我参加了几乎所有先生主持的午餐对谈和学术会以,并且旁听了他作为主讲人之一的讨论课,东亚法律与社会(Seminar: Law and Society in East Asia)。柯恩教授不仅是中美法律交流的奠基人、中国法研究的泰斗,更是我的恩师、吾辈楷模。下面,我还是依照他的习惯,称呼他Jerry。

2018年初,我刚获得富布赖特访问学者的资助,但在寻找访学机构时遇到了困难。第一次联系Jerry,是想冒昧地请他帮忙询问另一所研究机构的情况,心中不免忐忑。没想到, Jerry很快回信并答应帮忙。后来,当Jerry得知这所机构已经满员之后,便立即询问我是否有兴趣申请美亚法研究所。我当时深感荣幸,加之临近资助方要求的截止日期,便欣然应允。然而,彼时美亚法研究所招收访问学者的期限已过。最终,在Jerry和时任执行主任柏恩敬(Ira Belkin)教授的共同努力之下,我才顺利拿到邀请函。对此,我一直心怀感激,也有不解:Jerry为何要如此帮助一位素未谋面的青年学者?来到纽约大学,亲眼目睹他如何与学生、与后辈学者相处,我才明白,这就是Jerry的常态,与人交流,不论长幼,不论身份,总是平等相待,真诚热心,乐于关爱。

在纽约大学,听Jerry讲课是一种享受。他主讲的内容是中国法制发展史,尤以改革开放之后为主。每次开讲,他总是系着精致的领结,用富有磁性的嗓音——低沉而坚定——娓娓道来,如数家珍。最令我敬佩的是,已然88岁高龄的先生,从来不依赖讲稿,更不用PPT,40分钟不间断地讲述,滔滔不绝,思路清晰,逻辑严谨,期间甚至无需饮水小憩。几次课下来,我发现Jerry很少引经据典或讲大道理,他总是在摆事实、讲故事,最精彩的就是那些他亲历的故事,那真是他的故事(history)。有些片段至今依然记忆犹新,看着历史(他的故事)在课堂上、在我眼前栩栩如生地重现、展开,震撼之感,难以言表。这或许就是Jerry治学和传道的哲学,一种看似至简实则深邃的经验哲学:最可靠、最极致的经验就是他自己亲历的经验;不是那种浮于表面的、常常被我们批评的“经验主义”,而是经过思辨、经过沉淀、经过验证的人生智慧与历史洞见。

这种哲学也贯穿在他每周一主持的“每周亚洲法:午餐对谈”(Asia Law Weekly Lunch Dialogue)。每次对谈,都是一场盛宴。首先是字面意义上的盛宴,因为Jerry一直坚持为大家订中餐外卖。在曼哈顿,这样的花费可不菲。后来我才知道,Jerry的坚持并不是因为经费充裕,也不是为了吸引听众,而是源于一份对中国文化的尊重,希望美国学生能更好地感受其中韵味。当然,这更是学术的盛宴。与严谨的讨论课相比,这里的氛围更加发散、更加随性。Jerry邀请的嘉宾来自各行各业,不局限于学术界。对谈也并非嘉宾主讲,而是在他引导下的开放式交流。Jerry总是习惯从嘉宾的人生经历或治学经历谈起,然后层层递进、逐步深入。顺着Jerry的思路,一副世界眼中的中国图景徐徐展开。听众不仅能与嘉宾共情,感受他们的中国法情缘,更能体会Jerry的真性情——他对中国文化和法治发展的真挚的、深沉的爱。

2019年访学结束之际,我本想和Jerry好好畅谈这一年的收获,可惜他恰好外出度假。当时以为自己很快还会再来纽约,未曾想自此世事变幻,这竟是永别。于我而言,Jerry是学界前辈的楷模,是大学教师的楷模,是中国法研究的楷模。或许,缅怀Jerry最好的方式,就是像他一样,以热忱之心对待寻求帮助的学生;像他一样,以亲身体悟探寻法学的真谛,像他一样,对中国法治的进步与发展永怀热爱与期待。

孙平

华东政法大学法律学院副研究员

纽约大学法学院亚美法研究所富布莱特访问学者

-

Chi Yin Lawyer, former U.S.-Asia Law Center research scholar:

Jerry was a giant of a man with immense warmth for ordinary people and a special love for China. One of my greatest fortunes is to have worked with him over the past twelve years at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute. From my first encounter with him, when I was a student in his seminar “Law and Society in China: Criminal Justice in American Perspective,” he always treated me collegially. Despite his vast knowledge and experience, he showed genuine interest in my observations as a young former judge from China.

I clearly remember the sunny afternoon before graduation when he called me to his office. “Do you want to work with me at the institute?” he asked. I was so thrilled that my reply was, “Can I give you a hug?” “You bet!” said Jerry, and with that began one of the most fulfilling chapters of my professional life. I learned a huge amount from Jerry, not only by working with him on articles and cases, but also by observing his kindness in interacting with people of all walks of life, including presidents and dissidents and business moguls.

I learned from his wisdom in separating the noise from the essence in U.S.-China relations, and from his optimism about China and Chinese people. Working with Jerry was like being invited to join Ethan Hunt’s team on seemingly impossible missions. He galvanized us and united us behind his ambitious goal of improving understanding across the Pacific. Jerry’s passion and compassion were contagious. His influence will continue to be felt for a long, long time.

-

I am chiming in late to the many heartfelt tributes to Jerry Cohen, but I wanted to highlight one of his very important and very early contributions to research on contemporary China that I believe has only been mentioned once in earlier tribute emails to Jerry: At the young age of 33, and only beginning to retool himself as a China scholar himself, Jerry was the founder of the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, in 1963. I will only mention a few details here, but for those not familiar with the "old USC" (1963-1988), Ezra Vogel published an account of the USC founding in The China Journal in its January 2016 issue, following the 50th anniversary of the USC founding. (Perennial funding problems eventually led to the old USC ceasing operations in 1988, with the Chinese University of Hong Kong establishing a modified version housing the USC library collections and other materials, where the USC Center for Chinese Studies continued operating until 2020, when the CUHK decided to eliminate it as a separate entity and merge its collections with the general library.)

Jerry was in Hong Kong in 1963, trying to interview PRC refugees for what would eventually become his masterful book on criminal law and process in the PRC, and following initiatives from various, mainly American, foundations, to found and fund a research center for the study of the PRC "at a distance," from Hong Kong, those involved eventually asked Jerry to find facilities and establish what would eventually become the USC. Initially he rented space next to the Peninsula Hotel, but soon after he was able to arrange to move the USC to its decades-long location, at 155 Argyle St. in Kowloon. Jerry also negotiated to have the archived Chinese newspaper and classified clipping files of the Chinese press that the nearby Union Research Institute had already been accumulating available for USC scholars to use (with the USC van ferrying requested URI materials back and forth between that facility and the USC on a regular basis.)

I believe Jerry only remained in Hong Kong for the 1963-64 year, but the advisory committee of the USC then hired a series of directors to keep the new institution going. By the time I arrived in Hong Kong and began interviewing PRC refugees for my Harvard doctoral thesis, in 1968, it was already thriving. Since American students and academics trying to research the PRC, and many of their counterparts from other countries, could not even visit the PRC until after 1972, and could not conduct research within China until after 1979, the USC quickly became the main institutional base for a wide range of junior and senior China researchers. Only a minority of USC scholars such as myself mainly relied on refugee interviewing, but others doing documentary research (even on pre-1949 China) or even ethnographic fieldwork in Hong Kong villages, gravitated to the very lively and internationally diverse grouping of China researchers working at the USC at any particular time. I myself returned to Hong Kong and the USC two more times, in 1973-74 (oddly, also serving as titular USC director that year, although by then John Dolfin was actually running the place) and then in 1978-79, and from my three stints came my first three books published on contemporary China (the latter two co-authored with Bill Parish) as well as many articles. I believe others have made estimates of the impact of the old USC, even after research within China became possible, that indicate that a very high proportion of all books and articles on the PRC published in those years involved at least some time spent conducting research at the USC. So Jerry's role in establishing the USC in 1963 had incredible payoffs in terms of the original China research that institution generated and facilitated, long after Jerry had handed the USC leadership role to others. I can't imagine that the blossoming of contemporary China research before it was possible to conduct research within the PRC would have flourished so robustly without the wise decisions and early leadership Jerry Cohen provided.

For anyone interested, four years ago, as the USC at CUHK was being abolished, I contributed a personal recollection of my debt of gratitude to the old USC for a volume that Jean Hung was collecting:https://martinwhyte.scholars.harvard.edu/sites/g/files/omnuum2491/files/martinwhyte/files/the_usc_made_my_career_as_a_china_scholar.pdf

-

At the same time as Jerry’s friends and family were sitting shiva in NYC, I was just about to deliver some remarks at Princeton on the present state of U.S.-China relations. Of course I ended up devoting the first portion of my lecture to talking about Jerry. In particular what I wanted to impress on these highly accomplished and talented students was how astounding it was that someone who had clerked for both Frankfurter and Warren and was on a glide path to a pretty cushy life in the legal elite would essentially start over at 30 with the almost inexplicable decision to commence Chinese language study etc. And then many years later, for him to leave his chair at Harvard Law (where he had been almost selected as Dean) to go open the first American law office in Beijing. I mean, who does that? For the life of me I can’t think of anyone else who has exhibited that same level of vision, confidence, and sense of adventure in their professional choices at that level of the game.

At Princeton, I also had a chance to catch up with my mentor Stan Katz, himself 91 and still going strong. He wanted to impress upon me that in the 1960s, Jerry was in charge of how to apportion the funds of the Charles Warren Chair in American Legal History at Harvard Law. He used that opportunity to bring three young scholars to HLS for the year, Morton Horowitz, Bill Nelson, and Stan Katz, who in Stan’s telling spent the year in constant conversation with one another and eventually planning a major symposium at the end of the year where they got Willard Hurst to come deliver the keynote address. To Stan, this whole experience was a pivotal moment in the development of legal history as a robust field in American law schools, one that probably on the whole surpasses our own field of Chinese law in general prominence. And just as an aside, almost, Jerry was there at the beginning, playing a pivotal role. Just another item to add to the long list of ”wait, Jerry did that too??” that I imagine is similarly mind boggling to anyone who knows how he brought our particular field to life (which would have been incredibly impressive just on its own).

The last thing I’m compelled to highlight is how seriously Jerry took his many friendships in China itself. I can think of only two people, Jerry and Andy Nathan, who have modeled to such an impressive level the ability to both be extremely (and appropriately) critical of China as needed and at the same time to maintain genuinely warm ties with many who are still part of the system in China. Every time I have gone to China in recent years I have carried back well wishes from his many friends there and in turn have taken the same back from him to them. One friend who recently retired from the SPC messaged me as soon as she heard the news the other day to say that she had to stop her car on the side of the road in order to weep at his passing.

What an incredible life he lived, what an incredible legacy he leaves us.

-

I haven't written in, mostly as I have been lapping up all of the wonderful thoughts and expressions of love and true regard for Jerry, and trying to think clearly about what he meant in our lives, and my life.

I first met him in Shanghai when I was at Fudan University, in the Fall of 1983, when I bicycled from Wu Jiao Chang to the home of one of my friends (Pan Shizi, the last Dean of St. Johns who returned to China in the 1930s with a law degree from Cambridge (UK), keen to make a contribution to the "New China," but who, after the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the GPCR, and 10 years in solitary outside of Shanghai, was pretty doubtful of Jerry's bubbling confidence that a legal system, much less "rule of law," was coming to China).

Jerry was in recruitment mode that evening (when was he not in recruitment mode?), and as with so many others on this list, he directed me to give up dreams of a doctorate in late imperial Chinese literature and enroll at the Columbia Law School, where Jerry's former number 2 at HLS and EALS, equally wonderful Randy Edwards, was assembling a strong cohort of Chinese language-competent/Chinese law-curious law students. I joined Jerry at Paul, Weiss, really at the end of his practice career and as he transitioned back into the academy (at NYU), but we had so much fun together, working as lawyers, or just meeting when he came through London or Paris (when I was there) and of course China (when i was there), but also in so many other diverse and interesting circumstances (the tennis court, where he was an unfeeling monster; the Rijksmuseum where he first alerted me to Vermeer's genius; working on the first external review of the Ford Foundation's CLEEC program around China; Government House in Hong Kong with Chris Patten as he made his bold gamble on electoral reform before the Handover; climbing Taishan with Joan and slurping Lanzhou lamian at the top; on a very long flight to somewhere where he told me the truth about Justice Frankfurter (I'll never tell), and on and on and on...)

As many have said as the remembrances and tributes pour in, Jerry was (for me at least) defined by his generosity of spirit, a generosity he applied to the study of a foreign (non-US) political economy and political legal system just as much as he applied it to us. There is no doubt that he was correct to claim credit for the careers and lives many of us have lived (though he did engage in, and even laughingly acknowledge, a bit of over-claiming...), but whenever and however he encountered us, or supported us, or pushed us, or argued with us, or questioned us, he was generous, and so much fun.

I feel heartbroken to lose such a good friend in my life, but grasp, hard, to memories of fortunate and entirely unique interactions over more than 4 decades with a truly generous and singular soul. The English writer Julian Barnes once quipped, "I miss God." For my part, I miss Jerry.

-

Jerome (Jerry) Cohen was a true giant. Throughout his long and rich life he founded the study and practice of Chinese law in the U.S. He became a teacher and mentor to many. He always worked towards justice and engagement. He combined sharp brilliance with the best humor and warmth. I have been so fortunate to co-teach a seminar with him. He was more than a dear colleague. He became a true friend who would listen and share. He has also played a vital role in my career and has always continued to inspire me in my own research about China and analysis of root causes of harm and injustice. I will really miss Jerry and strive to carry all his wisdom and wit forward to the future. My thoughts go to Joan and his children, grand children, and great grandchildren.

-

My path crossed with Jerry’s when he published a review of an article of mine. I looked up to him, in awe of his knowledge and standing in the China law community; yet he always insisted that I called him “Jerry” instead of “Professor Cohen”, which took me a while to get used to! We finally met in person when I (at his prompting) visited USALI in 2023, and I had the privilege of having two long conversations with him over lunch at his home. His courage, wisdom, vision, kindness, generosity, curiosity, wit, love for Mrs. Cohen and pride in his family, deeply touched me. What a giant Jerry was; what an extraordinary life he has lived. His legacy will last, as will the memories about him. Much love and condolences to Mrs. Cohen and the family.

-

While he was a towering figure in China law circles and more broadly on Asia and China policy matters, Jerry was equally a generous colleague and mentor. I am honored to have received his kind support and encouragement over the years. Jerry will be greatly missed and his equal will not soon (if ever) be seen in this world.

-

I had the privilege of studying under Jerry at the NYU School of Law and staying in touch in the years that followed. In fact, his pioneering life in Chinese and comparative legal studies was a large part of why I decided to attend NYU in the first place. While the law student eventually became a practicing lawyer, I find that I have perpetually thought of myself as Jerry's student.

Jerry was intellectually sincere. His unshakeable moral compass was not at odds with his openness to dialogue or his ability to expound every idea into boundless, important questions. He was generous with his time, and he never let his prominence get in the way of his kindness or his humor.

Jerry was an intellectual giant, a wonderful teacher, a personal hero, and a friend. I will miss him dearly. May his memory be a blessing.

-

I will miss Jerry terribly. The late NYU Law Professor Jim Jacobs introduced me to Jerry as a New York State judge interested in comparative criminal law. As a result, Jerry introduced me to the Chinese criminal justice system by generously inviting me to participate in NYU’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute programs in both New York and China, which also led to my participation in the Dialogues on the Rule of Law & Human Rights conducted by the National Committee on US-China Relations. It has been a privilege to serve in both capacities and, in particular, an education and inspiration to watch Jerry candidly and fearlessly speak out in both forums. I treasured his friendship and will treasure his memory.