Tributes to Jerry Cohen

Jerome A. Cohen, professor emeritus at NYU School of Law and founding director of the U.S.-Asia Law Institute, touched countless lives during his remarkable career. Here is a collection of tributes from around the world. Read also USALI’s own tribute to Jerry, “Remembering Jerome A. Cohen: Field Builder, Rights Advocate, and Mentor.”

News Media

Wall Street Journal: “Jerome Cohen, the First American to Practice Law in China, Dies at 95,” Sept. 23, 2025.

South China Morning Post: “Jerome Cohen, respected China law expert – and regular critic – dies at 95,” Sept. 24, 2025.

Law.com: “Jerome Cohen, The Original 'China Hand', Dies At 95,” Sept. 24, 2025.

The Taipei Times, “Asian law expert Jerome Cohen, mentor to Taiwanese leaders, dies at 95,” Sept. 24, 2025

Focus Taiwan (CNA English News), “Jerome Cohen, mentor to prominent Taiwanese politicians, dies at 95,” Sept. 24, 2025

BBC Chinese service: “孔杰荣逝世:中国法律研究先驱的传奇人生,” Sept. 26, 2025.

New York Times: “Jerome Cohen, Lawyer Who Plumbed Chinese Legal System, Dies at 95,” Sept. 27, 2025.

The Economist: “China’s most optimistic critic,” Sept. 29, 2025.

The Provincetown Independent, “Renowned China Scholar Jerome A. Cohen Dies at 95,” Oct. 1, 2025.

Institutions and Government

U.S.-Asia Law Institute: “Remembering Jerome A. Cohen: Field Builder, Rights Advocate, and Mentor,” Sept. 23, 2025

East Asian Legal Studies at Harvard University Law School: “Tribute To Professor Jerome A. Cohen (1930-2025),” Sept. 23, 2025

NYU School of Law: “In memoriam: Jerome A. Cohen (1930-2025),” Sept. 24, 2025

Institutum Iurisprudentiae Academia Sinica: “In Memory of Professor Jerome A. Cohen, Emeritus Professor of Law at New York University School of Law,” Sept. 24, 2025

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ROC (Taiwan): statement on X, Sept. 24, 2025

Human Rights in China, “HRIC Mourns the Passing of Jerome A. Cohen, Pioneer of Chinese Law and Steadfast Ally of Human Rights,” Sept. 25, 2025.

Consulate General of Japan in New York: statement on Facebook, statement on Instagram, statement on X, Sept. 30, 2025

Council on Foreign Relations: “Jerome A. Cohen: Legal Pioneer, China Expert, Mentor, and Friend,” Oct. 1, 2025

Harvard Law School: “In memoriam: Jerome A. Cohen (1930-2025),” Oct. 3, 2025

Asia IP & Competition Law Center, UC Berkeley Law: “In Memory of Professor Jerome A. Cohen (孔杰荣教授, 1930–2025),” Oct. 9, 2025

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University: “Remembering Jerome A. Cohen (1930 – 2025),” Jan. 22, 2026.

Personal Tributes

呂秀蓮:敬悼 孔傑榮教授, Sept.24, 2025

許章潤:精神家族一代師表——思祭孔傑榮先輩:許章潤誄孔公 (English translation by G.R. Barmé), Sept.25, 2025

张千帆:中国法治的“不老松”——追忆孔杰荣教授, Sept.24, 2025. Click here for the English translation by Pekingnology, Sept. 28, 2025

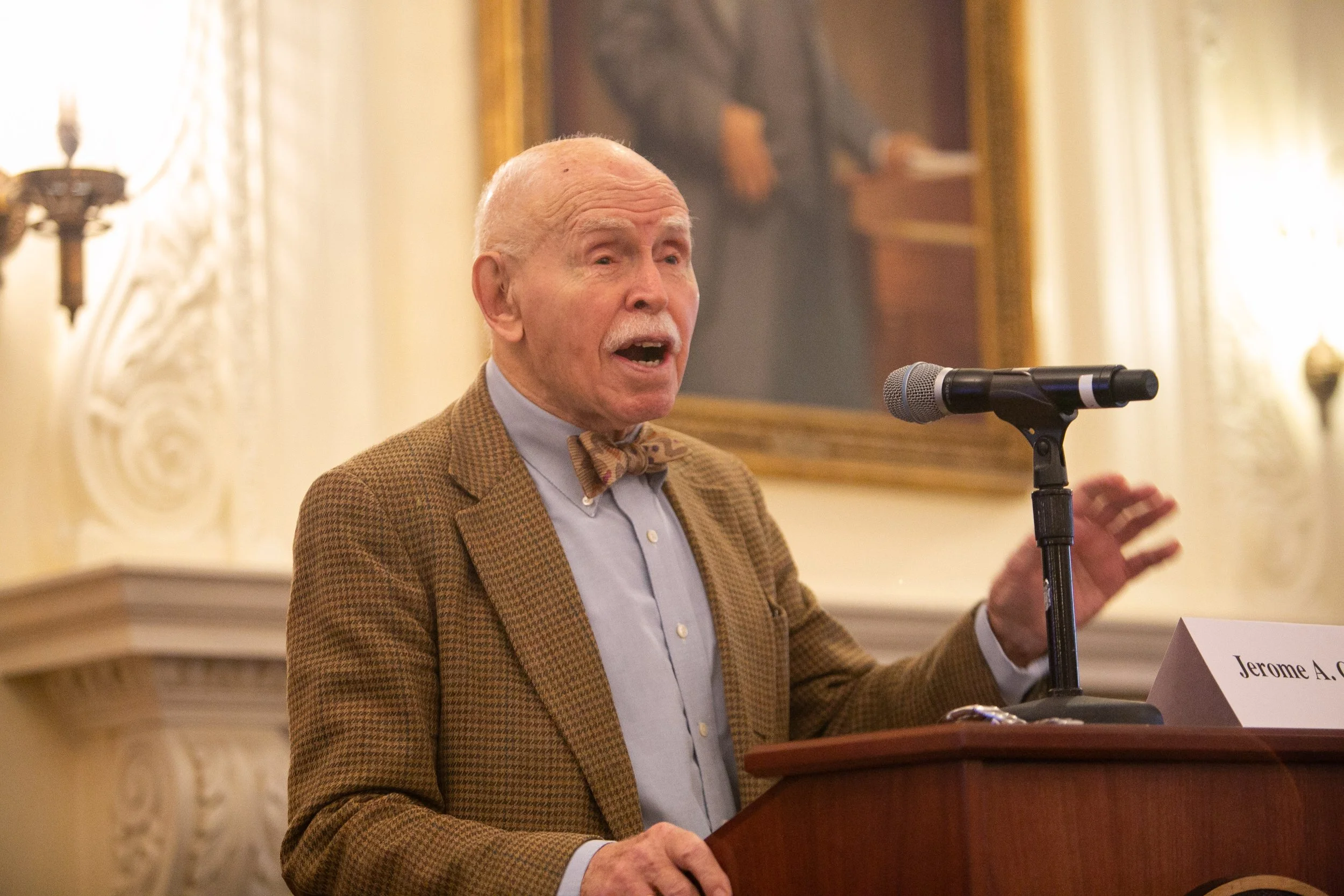

José E. Alvarez: Jerry Cohen: The Person, The Vision (speech delivered at an event celebrating the publication of Jerome A. Cohen's memoirs, Eastward, Westward: A Life in Law), June 24, 2025

Yang Jiangli: In Memory of Professor Jerome A. Cohen (1929–2025) A Guardian of Justice, A Bridge Across Worlds, Yibao Online, Oct. 3, 2025

Susan Finder: Professor Jerome Cohen (with links to multiple remembrances by other authors), Sept. 25, 2025

虞平:讣闻|找回“失去的中国”,中国法研究专家杰罗姆·柯恩去世,95岁, Caixin, Oct. 9, 2025

Remembering Jerome A. Cohen: A ChinaFile Conversation, Oct. 10, 2025

季美君:怀念睿智长者——柯恩教授,Oct. 31, 2025.

Click the "+" button to the right of each item to read the full tribute.

-

In Loving Memory of Professor Jerome Alan Cohen

Yun-chien Chang (Jack G. Clarke Professor of East Asian Law, Cornell Law School; LL.M 06’; J.S.D. 09’)

It is still difficult to believe that Jerry has left us.

I first met Jerry in his office in May 2009. In just a few days, I would return to Taiwan to hopefully begin an academic career. Jerry was already 75 years old at the time. Though he walked slowly, his voice remained resonant, full of humor and warmth, generously sharing his life’s wisdom with a junior colleague nearly half a century younger.

Little did I know that over the next decade, I would have the privilege of encountering Jerry in various corners of the world. Once, I attended a panel discussion he was moderating. I had expected the typical format—a moderator who simply keeps time and ensures speakers take turns. But Jerry elevated the role of “moderator” to a level that was surely unprecedented. He would interject at just the right moment with sharp, insightful commentary. He asked questions that drew out the best in each speaker and called on participants with an uncanny intuition for their perspectives and areas of expertise. It was clear that he knew everyone in the room—who they were, what they thought, and how to bring them into the conversation at just the right moment. His ability to orchestrate such a high-efficiency, intellectually rich exchange left me speechless. After the session, I told him how amazed I was. He smiled and replied in Mandarin: “我是老狐狸了” (“I’m an old fox”). Some of the tributes written about him since his passing have mentioned how adept he was at using Chinese idioms—this was one such moment I will never forget.

Throughout the 2010s, whenever I passed through New York for conferences, Jerry never hesitated to invite me to give a lunch talk at NYU Law, my Alma mater. I had imagined a typical format where I would present a coherent academic narrative and field a few scattered questions from the audience. But of course, that wasn’t Jerry’s style. He said, “Let me interview you.” I asked how I should prepare. He said, “There is no need for you to prepare. Your whole life is your preparation.” For a young scholar, that was both thrilling and terrifying. I certainly hadn’t spent my whole life preparing for a lunch talk! But the session unfolded under Jerry’s wise, witty, and perfectly paced questions—and I found myself responding more freely and insightfully than I could have imagined. A few years later, we repeated the same format at again. This time, Jerry asked entirely different questions, drawing out a different set of reflections—almost as if this man, then in his late 80s, had remembered every word I had spoken years earlier.

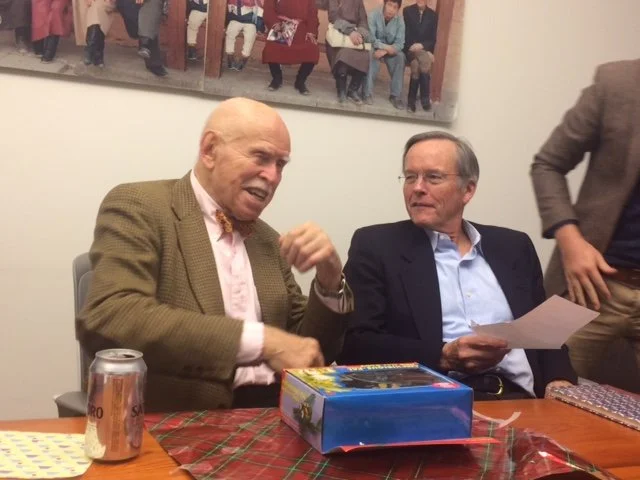

In the spring of 2019, I returned to NYU Law School as a Global Professor. Jerry, then 89 and not yet retired, invited my wife, son, and me to dinner on our second night in New York. The photo we took that evening captures a moment I will always treasure. After dinner, he and his beloved wife Joan graciously welcomed us into their home—a home that felt more like a private museum. The way he had arranged the artwork, and the stories he told about each piece, left us spellbound. My favorite museum in the UK is the Sir John Soane Museum, a compact but remarkable space near the British Museum—created by a man of many talents who turned his home into a personal museum and opened it to the public after his death. Visiting Jerry’s home felt like stepping into the Soane Museum—with the rare privilege of having the master himself as our guide.

Now, that voice is gone.

I’ve been reflecting: if someone like me, who came into Jerry’s life relatively late, received so much of his generosity, care, and encouragement, then how much more joy and love must he have spread to others—both the great figures of his generation and younger colleagues like myself? As I read through the tributes on news sites, in email threads, and across social media, I find story after story, each full of warmth and gratitude. I think I now understand the answer.

Jerry Cohen’s life was a gift to us all.

-

Professor Jerome A. Cohen and Taiwan’s Democratization Process

Chang-fa LO (Former Permanent Representative to the WTO; former Constitutional Court Justice; and former Dean of National Taiwan University College of Law)

With vision, courage, and wisdom, Professor Jerome A. Cohen—Jerry—had a deep and lasting bond with Taiwan’s struggle for democracy and human rights. His engagement went far beyond scholarship. It was a lifelong friendship with the people and ideals of Taiwan.

I had the great honor of working with Jerry and Professor William P. Alford in editing Taiwan and International Human Rights: A Story of Transformation. In his chapter, “Taiwan’s Political-Legal Progress: Memories of the KMT Dictatorship,” Jerry shared his vivid memories of Taiwan’s journey from authoritarianism to democracy.

Jerry’s first visit to Taiwan was in 1961, sixteen years after the Nationalist Government arrived from the mainland. He found a “dilapidated” island, yet one that awakened his passion for comparative law and China’s legal culture. During later visits under martial law, he witnessed both repression and the gradual emergence of hope.

In the 1980s, Jerry became directly involved in Taiwan’s human rights struggles. He supported democracy advocate Annette Lu (later Taiwan’s Vice President), who was imprisoned after the 1979 Kaohsiung Incident, and his lobbying contributed to her release in 1985. He also represented the widow of Henry Liu (Jiangnan), a journalist assassinated in California by Taiwan’s intelligence agents, using the case to expose martial-law abuses and draw global attention to the dangers faced by critics of the regime.

Jerry also mentored many of Taiwan’s future leaders, including Ma Ying-jeou, who later became president. Through his teaching and friendship, he helped shape a generation of legal minds committed to democracy and the rule of law.

Even after Taiwan’s democratic transition, Jerry remained devoted. He served on the International Review Committees of Experts in 2013 and 2017 to assess Taiwan’s human rights progress, lending his credibility and encouragement to the island’s continuing efforts.

In 2017, during a lecture at National Taiwan University College of Law, Jerry emphasized that Taiwan’s transformation from authoritarianism to democracy offered valuable lessons for the world. The resulting book, Taiwan and International Human Rights, later received the 2020 Certificate of Merit from the American Society of International Law. This is a testament to his leadership and inspiration.

For Taiwan, Jerry was never an outsider. Through his vision, empathy, and steadfast commitment, he became an important part of our democratic story. To me, he was a scholar and practitioner whose deep humanistic spirit infused everything he taught, wrote, and lived.

-

In memory of Jerome A. Cohen (1930-2025): Jerry, as I remember

The passing of Professor Jerry Cohen is a profound loss, not only to the field of Chinese law studies but also to many of us personally. Friends and colleagues have shared numerous tributes, attesting to the significant impact of his life. We remember Jerry—as he preferred to be called—as a community. Now that he has left us, we become the keepers of his memory. And we pass this memory on by telling Jerry’s stories, as he, a storyteller, would have liked us to do.

Working for Jerry at NYU in the previous decade—though he’d always graciously insist it was “working with”—was a great privilege, allowing me to witness an extraordinary man in action. To share those memories, perhaps the Chinese term 喜怒哀樂 (joy, anger, sorrow, and happiness), capturing the most fundamental emotions of life, is a fitting place to begin.

Joy

With his signature bow tie and dignified mustache, Jerry appeared serious and even a bit intimidating at first glance, but once conversations started, you knew he was full of joy, had a great sense of humor, often accompanied by a mischievous twinkle in his eyes, and treated those around him with warmth, kindness and humanity. I believe his secret life recipe was a genuine interest in everyone he met.

Jerry, for example, liked “interrogating”—in his own words—guest speakers at the weekly lunch meetings he hosted at NYU’s US-Asia Law Institute, one of his favorite activities. During those conversations, he would get personal, asking where they were born, what it was like growing up there, why they studied law or China (or both), and what motivated them to pursue their chosen path. Jerry was genuinely curious about the stories of people; each one, he believed, had something unique to tell.

Jerry himself famously loved telling stories (and jokes), and they never failed to fascinate us. It was remarkable how he was able to use a story to illuminate something larger, though he also loved a good story simply for the joy of it. Among his immense repertoire, some were all-time favorites, inevitably summoned more than once or twice. As Jerry knew, we junior colleagues even schemed to create a code system where each joke had a number, so he only needed to call out the number, and we could all laugh without missing a beat!

Anger

I rarely saw Jerry angered, but when he was, he was fierce.

Whenever Jerry traveled to China, he always made a point of visiting Chinese human rights lawyers, despite the obstacles. In 2010, Jerry went to see the Shanghai human rights lawyer Zheng Enchong, who had been under house arrest for years (he had tried visiting him previously but was stopped by the police). As Jerry and I approached lawyer Zheng’s apartment, we were, unsurprisingly, blocked by several plainclothes police officers in the courtyard. Jerry kept asking what legal basis they had to prevent us from seeing a supposedly free Chinese citizen. As the argument escalated, Jerry grew increasingly outraged. He did not back down. He was determined to see lawyer Zheng this time. After intense negotiation, we agreed to come back the next day, finally getting to see Zheng and his family. The police likely did not want to contend any longer with Jerry’s wrath.

Sorrow

As Jerry wrote in his memoirs, he was born in 1930 into a middle-class Jewish family in New Jersey. Both his father and mother came from immigrant families from Europe. Jerry lost several relatives in the Holocaust during WWII. Even after the war, Jewish people in America continued to face various forms of discrimination.

In one group meeting where a Chinese anti-discrimination advocate was invited to speak, Jerry introduced the speaker and emphasized the importance of this topic. He began to relate it to his family’s experience. In the middle of a sentence, he suddenly stopped talking, and the room fell silent—for the first time, we saw Jerry cry, overwhelmed by emotion. I often wondered if this personal experience had played a significant role in motivating his work on human rights, rooted in his deep compassion.

Happiness

Nothing brought Jerry more happiness than knowing he helped others. He did this with great satisfaction and a sense of purpose. When Jerry was asked what he was most proud of in his long career, instead of mentioning his groundbreaking scholarship in Chinese law or his pioneering role as the first foreign practicing lawyer in China, he spoke about helping people and, at critical moments in history, intervening to save some of them from dire circumstances.

Many colleagues have recounted how Jerry literally changed their lives (mine included). He would bring people to the field, make introductions for them, find scholarships, provide references, and help them secure positions where they could contribute. He saw great potential in people, even for those of us who could not see it ourselves.

Jerry’s happiness came from the community he built, a community inspired and uplifted by his supportive hand. He liked the phrase, “He who acts through another, acts himself.” This is very true. As Don Clarke said, Jerry “lives on in a very real way in the people and institutions he fostered over the years.”

In one of the early meetings, I asked Jerry what I should do with my life. He said, “Do something that interests you, something you can take responsibility for, and, most importantly, something meaningful.” He led by example—again and again, in countless ways—through his extraordinary life.

-

I first came to know Professor Cohen through his academic works in the mid-1980s when I began my study of Chinese law in Sydney, Australia. It has been a great privilege and honour to know him on a personal level and to maintain contact (though, regrettably, too infrequently) with him since the 1990s. It saddens me deeply that I will never be able to meet him again.

He was not just a great scholar, teacher, and legal practitioner; he has always been an inspiration for all who aspire to be decent persons and who care about justice and human compassion. The passing of this giant is the end of an era, and the world is now much poorer without Jerry.

RIP, Jerry, we will all miss you and remember you!

Jianfu Chen

Honorary Professorial Fellow, University of Melbourne School of Law

Emeritus Professor, La Trobe University

-

As someone who as a young scholar in Hong Kong entered upon human rights advocacy and scholarship in the late 1980s, Jerome Cohen, or Jerry as we all know him, is someone who was always there. He was to us all the "father of China law studies." He was also very much a supporter of Hong Kong. As someone who was busily working on developing the rule of law in China in Deng Xiaoping's reform era, Jerry initially appeared cautiously optimistic about China's commitments to Hong Kong. That optimism would soon fade. I recall some years after the handover, when he was in Hong Kong to speak at the University of Hong Kong, another university in Hong Kong declined to host both Jerry and me, judging our views were too controversial for the times. By those days Jerry was working hard on behalf of human rights defenders in China. When we were declined for that other event we took to a coffee shop to commissorate about our rejection and appreciate that such rejections usually signals you are doing something right..

Jerry was of course not deterred in his advocacy and support for China and Hong Kong. I personally found myself invited several times to speak on Hong Kong and Tibet issues at his US-Asia Law Institute at New York University, where I am still an affiliate scholar. During those visits I was able to spend time with him and Joan at their home on the Upper East Side in New York. He was always so magnanimous in sharing his China law journey, regaling us with stories of the early days, many of which were reflected in the pictures and paintings on his apartment walls. I was struck by his sharp memory of that journey and his informed analysis of current developments. As my daughter, Hana, at 22 had just published a memoir of her growing up during the protests in Hong Kong, I joked with Jerry that he should have started sooner on his own memoir. I am happy to say that he finished that this year and it is well worth reading for anyone who wants to understand the importance of the rule of law: Eastward, Westward, A Life in Law. I last visited Jerry months ago at his old family home on Cape Cod. Even though he was not well, I was again struck by how well read and up to date he was discussing his current concerns about developments in China, seemingly looking past his emerging health challenges. Our loss is also a great loss for China.

-

In Loving Memory of My Mentor, Professor Jerome A. Cohen

On the morning of September 24, I was shocked and deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Professor Jerome A. Cohen. Memories of my time with him flooded back. From 2018 to 2019, with his generous help, I had the privilege of spending a year as a visiting scholar at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute (USALI) of NYU School of Law. During that year, I attended nearly all the lunch dialogues and conferences he hosted and audited his seminar, “Law and Society in East Asia.” Professor Cohen was not only a founding figure in U.S.-China legal exchange and a giant in Chinese law studies, but he was also my mentor and a role model for my generation. From here on, as was his preference, I will call him Jerry.

In early 2018, I had just received a Fulbright grant but was struggling to find a host institution. The first time I contacted Jerry, I ventured to ask if he could help inquire about another research institute on my behalf, and I couldn't help but feel apprehensive. To my surprise, Jerry replied quickly and agreed to help. Later, when he learned that the institution was overloaded, he immediately asked if I would be interested in applying to the USALI. I felt deeply honored and, with the deadline from my grant sponsor approaching, I gladly accepted. However, the application period for visiting scholars at the Institute had already closed. In the end, it was only through the joint efforts of Jerry and the then-Executive Director, Ira Belkin, that I successfully received an invitation. I have always been deeply grateful for this, but I was also wondered: why would Jerry go to such lengths to help a young scholar he had never met? It wasn't until I arrived at NYU and witnessed how he interacted with students and junior scholars that I understood. This was simply who Jerry was: he treated everyone as an equal, regardless of age or status, always with sincerity, warmth, and a readiness to show care.

Listening to Jerry's lectures at NYU was a pure pleasure. His main topic was the history of China's legal system, with a focus on the period after the Reform and Opening-Up. He would always begin his talks wearing an elegant bow tie, his magnetic voice—deep yet firm—speaking eloquently, as if recounting treasures from memory. What I admired most was that, at the age of 88, he never relied on notes, let alone a PowerPoint. He could speak for 40 minutes, his thoughts flowing clearly and logically, without even needing a sip of water. After a few classes, I realized that Jerry seldom quoted classical texts or lectured on grand theories. He was always presenting facts and telling stories, and the most captivating of all were the ones he had been there—they were truly histories. I still vividly remember certain moments. Watching history—his story—come to life and unfold before my very eyes in the classroom was a mind-blowing experience that is hard to put into words. Such, perhaps, was Jerry's philosophy of scholarship and teaching: an empirical philosophy, seemingly simple yet deeply profound. The most reliable and ultimate form of experience was his own. This was not the superficial "empiricism" we often criticize, but rather a lifetime of wisdom and historical insight, refined through reflection, contemplation, and verification.

This philosophy also permeated the "Asia Law Weekly Lunch Dialogue" he hosted every Monday. Each dialogue was a feast. First, it was a literal feast, as Jerry always insisted on ordering Chinese takeout for everyone. In Manhattan, this was no small expense. I later learned that his persistence was not due to an ample budget or a gimmick to attract attendees, but rather stemmed from a deep respect for Chinese culture and a wish for American students to better taste its richness. Of course, it was also an intellectual feast. Compared to his seminar, the atmosphere here was more relaxed and free-flowing. Jerry’s guests came from all walks of life, not just academia. It was an open conversation guided by Jerry rather than one-way presentations. He would always begin by asking about the guest's life or scholarly journey, then delve deeper, layer by layer. Following his line of thought, a panorama of China as seen through the world's eyes would unfold. The audience could not only empathize with the guests and their connections to Chinese law but could also feel Jerry's true character—his sincere and profound love for Chinese culture and the development of China’s rule of law.

As my visit came to an end in 2019, I had hoped to have a good talk with Jerry about my year's experiences, but he happened to be away on vacation. At the time, I assumed I would be back in New York soon. Little did I know that with the unpredictable turns of the whole world, it would be our final farewell. To me, Jerry was the epitome of an academic mentor, a university educator, and a scholar of Chinese law.

Perhaps the best way to remember Jerry is to be like him: to treat students seeking help with the same warmth and enthusiasm; to seek the true essence of law through personal experience; and to always hold a deep love and anticipation for the progress and development of the rule of law in China.

Sun Ping

Associate Research Professor, School of Law, East China University of Political Science and Law

Fulbright Visiting Scholar, U.S.-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law (2018-2019)

深切缅怀恩师柯恩(Jerome A. Cohen)教授

9月24日晨,惊悉柯恩(Jerome A. Cohen)教授溘然长逝,不胜悲痛。与先生交往的点点滴滴瞬间涌上心头,思绪万千。2018至2019年,我有幸在先生的帮助下,于纽约大学法学院美亚法研究所(U.S.-Asia Law Institute)访学一年。期间,我参加了几乎所有先生主持的午餐对谈和学术会以,并且旁听了他作为主讲人之一的讨论课,东亚法律与社会(Seminar: Law and Society in East Asia)。柯恩教授不仅是中美法律交流的奠基人、中国法研究的泰斗,更是我的恩师、吾辈楷模。下面,我还是依照他的习惯,称呼他Jerry。

2018年初,我刚获得富布赖特访问学者的资助,但在寻找访学机构时遇到了困难。第一次联系Jerry,是想冒昧地请他帮忙询问另一所研究机构的情况,心中不免忐忑。没想到, Jerry很快回信并答应帮忙。后来,当Jerry得知这所机构已经满员之后,便立即询问我是否有兴趣申请美亚法研究所。我当时深感荣幸,加之临近资助方要求的截止日期,便欣然应允。然而,彼时美亚法研究所招收访问学者的期限已过。最终,在Jerry和时任执行主任柏恩敬(Ira Belkin)教授的共同努力之下,我才顺利拿到邀请函。对此,我一直心怀感激,也有不解:Jerry为何要如此帮助一位素未谋面的青年学者?来到纽约大学,亲眼目睹他如何与学生、与后辈学者相处,我才明白,这就是Jerry的常态,与人交流,不论长幼,不论身份,总是平等相待,真诚热心,乐于关爱。

在纽约大学,听Jerry讲课是一种享受。他主讲的内容是中国法制发展史,尤以改革开放之后为主。每次开讲,他总是系着精致的领结,用富有磁性的嗓音——低沉而坚定——娓娓道来,如数家珍。最令我敬佩的是,已然88岁高龄的先生,从来不依赖讲稿,更不用PPT,40分钟不间断地讲述,滔滔不绝,思路清晰,逻辑严谨,期间甚至无需饮水小憩。几次课下来,我发现Jerry很少引经据典或讲大道理,他总是在摆事实、讲故事,最精彩的就是那些他亲历的故事,那真是他的故事(history)。有些片段至今依然记忆犹新,看着历史(他的故事)在课堂上、在我眼前栩栩如生地重现、展开,震撼之感,难以言表。这或许就是Jerry治学和传道的哲学,一种看似至简实则深邃的经验哲学:最可靠、最极致的经验就是他自己亲历的经验;不是那种浮于表面的、常常被我们批评的“经验主义”,而是经过思辨、经过沉淀、经过验证的人生智慧与历史洞见。

这种哲学也贯穿在他每周一主持的“每周亚洲法:午餐对谈”(Asia Law Weekly Lunch Dialogue)。每次对谈,都是一场盛宴。首先是字面意义上的盛宴,因为Jerry一直坚持为大家订中餐外卖。在曼哈顿,这样的花费可不菲。后来我才知道,Jerry的坚持并不是因为经费充裕,也不是为了吸引听众,而是源于一份对中国文化的尊重,希望美国学生能更好地感受其中韵味。当然,这更是学术的盛宴。与严谨的讨论课相比,这里的氛围更加发散、更加随性。Jerry邀请的嘉宾来自各行各业,不局限于学术界。对谈也并非嘉宾主讲,而是在他引导下的开放式交流。Jerry总是习惯从嘉宾的人生经历或治学经历谈起,然后层层递进、逐步深入。顺着Jerry的思路,一副世界眼中的中国图景徐徐展开。听众不仅能与嘉宾共情,感受他们的中国法情缘,更能体会Jerry的真性情——他对中国文化和法治发展的真挚的、深沉的爱。

2019年访学结束之际,我本想和Jerry好好畅谈这一年的收获,可惜他恰好外出度假。当时以为自己很快还会再来纽约,未曾想自此世事变幻,这竟是永别。于我而言,Jerry是学界前辈的楷模,是大学教师的楷模,是中国法研究的楷模。或许,缅怀Jerry最好的方式,就是像他一样,以热忱之心对待寻求帮助的学生;像他一样,以亲身体悟探寻法学的真谛,像他一样,对中国法治的进步与发展永怀热爱与期待。

孙平

华东政法大学法律学院副研究员

纽约大学法学院亚美法研究所富布莱特访问学者

-

Chi Yin Lawyer, former U.S.-Asia Law Center research scholar:

Jerry was a giant of a man with immense warmth for ordinary people and a special love for China. One of my greatest fortunes is to have worked with him over the past twelve years at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute. From my first encounter with him, when I was a student in his seminar “Law and Society in China: Criminal Justice in American Perspective,” he always treated me collegially. Despite his vast knowledge and experience, he showed genuine interest in my observations as a young former judge from China.

I clearly remember the sunny afternoon before graduation when he called me to his office. “Do you want to work with me at the institute?” he asked. I was so thrilled that my reply was, “Can I give you a hug?” “You bet!” said Jerry, and with that began one of the most fulfilling chapters of my professional life. I learned a huge amount from Jerry, not only by working with him on articles and cases, but also by observing his kindness in interacting with people of all walks of life, including presidents and dissidents and business moguls.

I learned from his wisdom in separating the noise from the essence in U.S.-China relations, and from his optimism about China and Chinese people. Working with Jerry was like being invited to join Ethan Hunt’s team on seemingly impossible missions. He galvanized us and united us behind his ambitious goal of improving understanding across the Pacific. Jerry’s passion and compassion were contagious. His influence will continue to be felt for a long, long time.

-

I am chiming in late to the many heartfelt tributes to Jerry Cohen, but I wanted to highlight one of his very important and very early contributions to research on contemporary China that I believe has only been mentioned once in earlier tribute emails to Jerry: At the young age of 33, and only beginning to retool himself as a China scholar himself, Jerry was the founder of the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, in 1963. I will only mention a few details here, but for those not familiar with the "old USC" (1963-1988), Ezra Vogel published an account of the USC founding in The China Journal in its January 2016 issue, following the 50th anniversary of the USC founding. (Perennial funding problems eventually led to the old USC ceasing operations in 1988, with the Chinese University of Hong Kong establishing a modified version housing the USC library collections and other materials, where the USC Center for Chinese Studies continued operating until 2020, when the CUHK decided to eliminate it as a separate entity and merge its collections with the general library.)

Jerry was in Hong Kong in 1963, trying to interview PRC refugees for what would eventually become his masterful book on criminal law and process in the PRC, and following initiatives from various, mainly American, foundations, to found and fund a research center for the study of the PRC "at a distance," from Hong Kong, those involved eventually asked Jerry to find facilities and establish what would eventually become the USC. Initially he rented space next to the Peninsula Hotel, but soon after he was able to arrange to move the USC to its decades-long location, at 155 Argyle St. in Kowloon. Jerry also negotiated to have the archived Chinese newspaper and classified clipping files of the Chinese press that the nearby Union Research Institute had already been accumulating available for USC scholars to use (with the USC van ferrying requested URI materials back and forth between that facility and the USC on a regular basis.)

I believe Jerry only remained in Hong Kong for the 1963-64 year, but the advisory committee of the USC then hired a series of directors to keep the new institution going. By the time I arrived in Hong Kong and began interviewing PRC refugees for my Harvard doctoral thesis, in 1968, it was already thriving. Since American students and academics trying to research the PRC, and many of their counterparts from other countries, could not even visit the PRC until after 1972, and could not conduct research within China until after 1979, the USC quickly became the main institutional base for a wide range of junior and senior China researchers. Only a minority of USC scholars such as myself mainly relied on refugee interviewing, but others doing documentary research (even on pre-1949 China) or even ethnographic fieldwork in Hong Kong villages, gravitated to the very lively and internationally diverse grouping of China researchers working at the USC at any particular time. I myself returned to Hong Kong and the USC two more times, in 1973-74 (oddly, also serving as titular USC director that year, although by then John Dolfin was actually running the place) and then in 1978-79, and from my three stints came my first three books published on contemporary China (the latter two co-authored with Bill Parish) as well as many articles. I believe others have made estimates of the impact of the old USC, even after research within China became possible, that indicate that a very high proportion of all books and articles on the PRC published in those years involved at least some time spent conducting research at the USC. So Jerry's role in establishing the USC in 1963 had incredible payoffs in terms of the original China research that institution generated and facilitated, long after Jerry had handed the USC leadership role to others. I can't imagine that the blossoming of contemporary China research before it was possible to conduct research within the PRC would have flourished so robustly without the wise decisions and early leadership Jerry Cohen provided.

For anyone interested, four years ago, as the USC at CUHK was being abolished, I contributed a personal recollection of my debt of gratitude to the old USC for a volume that Jean Hung was collecting:https://martinwhyte.scholars.harvard.edu/sites/g/files/omnuum2491/files/martinwhyte/files/the_usc_made_my_career_as_a_china_scholar.pdf

-

At the same time as Jerry’s friends and family were sitting shiva in NYC, I was just about to deliver some remarks at Princeton on the present state of U.S.-China relations. Of course I ended up devoting the first portion of my lecture to talking about Jerry. In particular what I wanted to impress on these highly accomplished and talented students was how astounding it was that someone who had clerked for both Frankfurter and Warren and was on a glide path to a pretty cushy life in the legal elite would essentially start over at 30 with the almost inexplicable decision to commence Chinese language study etc. And then many years later, for him to leave his chair at Harvard Law (where he had been almost selected as Dean) to go open the first American law office in Beijing. I mean, who does that? For the life of me I can’t think of anyone else who has exhibited that same level of vision, confidence, and sense of adventure in their professional choices at that level of the game.

At Princeton, I also had a chance to catch up with my mentor Stan Katz, himself 91 and still going strong. He wanted to impress upon me that in the 1960s, Jerry was in charge of how to apportion the funds of the Charles Warren Chair in American Legal History at Harvard Law. He used that opportunity to bring three young scholars to HLS for the year, Morton Horowitz, Bill Nelson, and Stan Katz, who in Stan’s telling spent the year in constant conversation with one another and eventually planning a major symposium at the end of the year where they got Willard Hurst to come deliver the keynote address. To Stan, this whole experience was a pivotal moment in the development of legal history as a robust field in American law schools, one that probably on the whole surpasses our own field of Chinese law in general prominence. And just as an aside, almost, Jerry was there at the beginning, playing a pivotal role. Just another item to add to the long list of ”wait, Jerry did that too??” that I imagine is similarly mind boggling to anyone who knows how he brought our particular field to life (which would have been incredibly impressive just on its own).

The last thing I’m compelled to highlight is how seriously Jerry took his many friendships in China itself. I can think of only two people, Jerry and Andy Nathan, who have modeled to such an impressive level the ability to both be extremely (and appropriately) critical of China as needed and at the same time to maintain genuinely warm ties with many who are still part of the system in China. Every time I have gone to China in recent years I have carried back well wishes from his many friends there and in turn have taken the same back from him to them. One friend who recently retired from the SPC messaged me as soon as she heard the news the other day to say that she had to stop her car on the side of the road in order to weep at his passing.

What an incredible life he lived, what an incredible legacy he leaves us.

-

I haven't written in, mostly as I have been lapping up all of the wonderful thoughts and expressions of love and true regard for Jerry, and trying to think clearly about what he meant in our lives, and my life.

I first met him in Shanghai when I was at Fudan University, in the Fall of 1983, when I bicycled from Wu Jiao Chang to the home of one of my friends (Pan Shizi, the last Dean of St. Johns who returned to China in the 1930s with a law degree from Cambridge (UK), keen to make a contribution to the "New China," but who, after the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the GPCR, and 10 years in solitary outside of Shanghai, was pretty doubtful of Jerry's bubbling confidence that a legal system, much less "rule of law," was coming to China).

Jerry was in recruitment mode that evening (when was he not in recruitment mode?), and as with so many others on this list, he directed me to give up dreams of a doctorate in late imperial Chinese literature and enroll at the Columbia Law School, where Jerry's former number 2 at HLS and EALS, equally wonderful Randy Edwards, was assembling a strong cohort of Chinese language-competent/Chinese law-curious law students. I joined Jerry at Paul, Weiss, really at the end of his practice career and as he transitioned back into the academy (at NYU), but we had so much fun together, working as lawyers, or just meeting when he came through London or Paris (when I was there) and of course China (when i was there), but also in so many other diverse and interesting circumstances (the tennis court, where he was an unfeeling monster; the Rijksmuseum where he first alerted me to Vermeer's genius; working on the first external review of the Ford Foundation's CLEEC program around China; Government House in Hong Kong with Chris Patten as he made his bold gamble on electoral reform before the Handover; climbing Taishan with Joan and slurping Lanzhou lamian at the top; on a very long flight to somewhere where he told me the truth about Justice Frankfurter (I'll never tell), and on and on and on...)

As many have said as the remembrances and tributes pour in, Jerry was (for me at least) defined by his generosity of spirit, a generosity he applied to the study of a foreign (non-US) political economy and political legal system just as much as he applied it to us. There is no doubt that he was correct to claim credit for the careers and lives many of us have lived (though he did engage in, and even laughingly acknowledge, a bit of over-claiming...), but whenever and however he encountered us, or supported us, or pushed us, or argued with us, or questioned us, he was generous, and so much fun.

I feel heartbroken to lose such a good friend in my life, but grasp, hard, to memories of fortunate and entirely unique interactions over more than 4 decades with a truly generous and singular soul. The English writer Julian Barnes once quipped, "I miss God." For my part, I miss Jerry.

-

Jerome (Jerry) Cohen was a true giant. Throughout his long and rich life he founded the study and practice of Chinese law in the U.S. He became a teacher and mentor to many. He always worked towards justice and engagement. He combined sharp brilliance with the best humor and warmth. I have been so fortunate to co-teach a seminar with him. He was more than a dear colleague. He became a true friend who would listen and share. He has also played a vital role in my career and has always continued to inspire me in my own research about China and analysis of root causes of harm and injustice. I will really miss Jerry and strive to carry all his wisdom and wit forward to the future. My thoughts go to Joan and his children, grand children, and great grandchildren.

-

My path crossed with Jerry’s when he published a review of an article of mine. I looked up to him, in awe of his knowledge and standing in the China law community; yet he always insisted that I called him “Jerry” instead of “Professor Cohen”, which took me a while to get used to! We finally met in person when I (at his prompting) visited USALI in 2023, and I had the privilege of having two long conversations with him over lunch at his home. His courage, wisdom, vision, kindness, generosity, curiosity, wit, love for Mrs. Cohen and pride in his family, deeply touched me. What a giant Jerry was; what an extraordinary life he has lived. His legacy will last, as will the memories about him. Much love and condolences to Mrs. Cohen and the family.

-

While he was a towering figure in China law circles and more broadly on Asia and China policy matters, Jerry was equally a generous colleague and mentor. I am honored to have received his kind support and encouragement over the years. Jerry will be greatly missed and his equal will not soon (if ever) be seen in this world.

-

I had the privilege of studying under Jerry at the NYU School of Law and staying in touch in the years that followed. In fact, his pioneering life in Chinese and comparative legal studies was a large part of why I decided to attend NYU in the first place. While the law student eventually became a practicing lawyer, I find that I have perpetually thought of myself as Jerry's student.

Jerry was intellectually sincere. His unshakeable moral compass was not at odds with his openness to dialogue or his ability to expound every idea into boundless, important questions. He was generous with his time, and he never let his prominence get in the way of his kindness or his humor.

Jerry was an intellectual giant, a wonderful teacher, a personal hero, and a friend. I will miss him dearly. May his memory be a blessing.

-

I will miss Jerry terribly. The late NYU Law Professor Jim Jacobs introduced me to Jerry as a New York State judge interested in comparative criminal law. As a result, Jerry introduced me to the Chinese criminal justice system by generously inviting me to participate in NYU’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute programs in both New York and China, which also led to my participation in the Dialogues on the Rule of Law & Human Rights conducted by the National Committee on US-China Relations. It has been a privilege to serve in both capacities and, in particular, an education and inspiration to watch Jerry candidly and fearlessly speak out in both forums. I treasured his friendship and will treasure his memory.

-

In Deep Remembrance of Professor Jerome A. Cohen

Tong Zhiwei, translated by Amy GaoI was deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Professor Jerome A. Cohen, the esteemed American jurist and former director of the NYU U.S.-Asia Law Institute, on the morning of September 24.

I first met Professor Cohen in the first half of 2002 while teaching at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Law and overseeing its academic affairs. Professor Cohen was a pioneer in advancing Sino-American legal exchanges, collaborative training of legal professionals, and cooperation in economic and trade legal system development during the latter half of the 20th century. He made groundbreaking contributions in these areas. Initially, he focused on developing the legal system in economic and trade relations, fostering exchanges and cooperation in legal education, and promoting the development of the legal profession between China and the United States. Later, he turned his attention to protecting individual rights within the criminal justice system. Although his ability to influence Chinese legal education, legal system development, and the protection of individual rights was limited as an American law professor, he undoubtedly exerted the greatest possible effort and achieved highly effective results within that limited space.

I enjoyed a friendship of more than 20 years with Professor Cohen, which was both collegial and mentor-like. While teaching at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and later at East China University of Political Science and Law, we collaborated effectively. He provided invaluable support and assistance. During my visiting scholar year at Columbia University in 2004, I frequently met with Professor Cohen and spent Christmas at his home. Over the years, I have been invited multiple times to deliver academic lectures, co-teach courses, and present specialized reports at New York University's U.S.-Asia Law Institute. On one occasion, he arranged a dialogue format session in which I discussed my academic journey and life experiences, with other attendees free to interject. Each time I met with Professor Cohen, participated in an event, or engaged in an academic exchange with him, I felt inspired and enriched. In 2018, despite his advanced age, he kindly wrote the foreword for my book Right, Power, and Faquanism: A Practical Legal Theory from Contemporary China (Brill, 2018), offering encouragement and recognition. Unfortunately, the Chinese edition of this book did not include his foreword for understandable reasons. Professor Cohen selflessly cared for the growth of younger generations of Chinese legal scholars. He was always willing to help and support them within his capacity, yet he never imposed on others, especially when it came to sensitive political matters. After interacting with him for many years, I came to appreciate his noble character and lofty moral qualities as a leading scholar in the field.

Professor Cohen sincerely cared about China's legal development and rule of law construction, hoping China's legal system would become increasingly sound and modernized. He made contributions worthy of our eternal remembrance. Through my interactions with him, I deeply felt that he genuinely wished for China's progress, prosperity, and the realization of good laws and sound governance. Fundamentally, he was a true friend of the Chinese people. Of course, the standards of progress, prosperity, and good governance held by different groups cannot be entirely the same. Professor Cohen also approached his work with the distinctive style characteristic of Western jurist and his own personal character. This inevitably led to some misunderstandings, though in hindsight these appear merely as minor episodes and secondary aspects.

Professor Cohen has now departed this world. I am deeply saddened that I cannot travel to New York to pay my final respects to him. I extend my deepest condolences to Professor Cohen’s family. May his soul rest in peace. Most importantly, I hope that future generations will carry forward the legacy he pioneered and tirelessly advanced, including Sino-American legal exchanges, the collaborative training of legal professionals, and cooperation in economic and trade law development.

深切悼念和缅怀柯恩教授

童之伟

9月24日早晨,惊悉德高望重的美国法学家、纽约大学亚美法中心原主任柯恩(Jerome A. Cohen)教授不幸过世,内心深感悲痛。

我是在上海交通大学法学院任教并主持法学院学术事务期间认识柯恩教授的,时间是2002年上半年。柯恩教授是20世纪下半叶推动中美法学交流、法律人才合作培养和经贸法制建设合作的先行者,在这些方面做出了开创性贡献。柯恩教授早年关注的是中美两国经贸方面的法制建设、法学教育方面的交流合作和律师业发展,后来转向了刑事诉讼制度中的个人权利保障。作为美国法学教授,他对中国法学教育、法制建设和个人权利保障等方面能发挥影响力的空间客观上是比较有限的,但他无疑在有限的空间内做了最大限度努力和最有成效的发挥。

我与柯恩教授有逾20年的友谊,可谓亦友亦师的关系。在我于上海交通大学法学院和华东政法大学任教期间,我们合作很好,他给过我宝贵的支持和帮助。2004年我在哥伦比亚大学做访问学者期间,与柯恩教授常见面,2004年那个圣诞节是在他家过的。历史上我先后多次应邀到纽约大学亚美法中心做学术讲座、同堂授课或专题学术报告,其中一次他还专门安排以与我对谈、其他与会者可随意插话的形式,让我谈自己的学术和人生。每次见到柯恩教授,每次办活动和做学术交流,我都觉得很有收获,很受鼓舞。2018年,他不顾高龄,为我的英文书“Right, Power, and Faquanism:A Practical Legal Theory from Contemporary China”(Brill 2018)写了前言,给予我肯定和鼓励。但十分可惜,因可以理解的原因,此书的中文版没有包含他的前言。柯恩教授无私地关心年轻一代中国法律学者的成长,总是愿意给他们提供力所能及的帮助、成全他们,但从来不强人所难,特别在敏感政治态度上。许多年来,我从与他的交往和他待人的言行中体会到了他作为前辈学术泰斗的伟大人格和高贵精神品质。

柯恩教授真诚关心中国的法律发展和法制建设,希望中国的法制能够日益健全、实现现代化,并为此做出了值得我们永远铭记的贡献。在与柯恩教授的交往中,我深深感到,他是真正希望中国进步繁荣和实现良法善治的。从根本上说,他是中国人民的真诚朋友。但显然,不同人群守持的进步繁荣和良法善治的标准不会完全一样,柯恩教授说话办事也有西方法律学者和他个人的独特风格。这就难免引起一些误解,好在现今看来都只是插曲和次要的方面。

柯恩教授与这个世界永别了,我无法前往纽约向他老人家做最后的致敬,这些都让我感到非常难过。我这里谨向柯恩教授的家人表示诚挚慰问。愿柯恩教授的在天之灵安息。我更希望,柯恩先生开创和一直致力于推动的中美法学交流、法律人才合作培养和经贸法制建设合作等方面的事业后继有人。

(作者现为广东财经大学特聘教授,原华东政法大学教授)

-

Jerry had been kind to me from day one. We first met in the mid-2000s when he gave a talk at the Foreign Correspondents' Club in Beijing. I was struck not only by his vast knowledge and expertise on China but also by how kind, approachable, and down-to-earth he was. At the time, I was a young journalist with limited understanding of China, yet in our conversations, he was always able to explain complex legal ideas in lay terms, and was always patient and gracious, even when I asked questions that might have seemed ignorant. Over the years, I interviewed him many times and asked for his insight on countless news stories, and he always responded promptly, eager to share his wisdom. Professionally, Jerry's insights were invaluable in deepening my understanding of China. Personally, his warm support and encouragement gave me the strength to carry on in my work. He was incredibly supportive when I decided to pursue a PhD, offering wise and helpful advice.

Despite being a prominent expert, Jerry never talked down to those more junior. He was always generous with his time, ready to encourage, inspire, and help others. With his passing, I have lost both a mentor and a friend. I will miss him deeply.

I was fortunate to have had the opportunity to chat with him online in August. He was pleased to hear that I would be writing a review of his memoir. It is a great shame he won't be here to see it, but it would be an immense honor for me to pay tribute to him in this way.

I’ll close with the opening paragraph of an interview piece I wrote for the South China Morning Post to mark his 80th birthday in 2010:

There is something unique about Professor Jerome Cohen, who turns 80 today. The pioneering US expert on the Chinese legal system was an early advocate of engagement with China, long before this became fashionable. And now, as the world is at the feet of China in awe of its economic might, he is one of the few who dare point out its shortfalls.

-

To Mr. Cohen: A Wise Bridge-Builder Between the Legal Communities of China and the United States

Sun Yuhua, translated by Amy Gao

On September 22, Eastern Time, Mr. Cohen closed his eyes forever—eyes that had once paved the way for the rule of law between China and the United States. Warm fragments of memories from my time studying in New York flood my mind like stars: the elder who always put younger scholars in the spotlight at roundtable dinners; the scholar whose office displayed a photograph with Premier Zhou Enlai; and the sage who devoted his life to fostering understanding between China and the United States. He has now quietly taken his final bow.

I vividly recall accompanying Professor Tong Zhiwei on our first visit to his office, where that yellowed photograph of him with Premier Zhou Enlai stood out prominently. He once shared with me that during his time at Harvard, he wrote to Dr. Henry Kissinger, passionately arguing for the profound significance of Sino-American diplomatic relations in reshaping the global landscape. This visionary foresight, transcending its era, made him a pivotal force in advancing the normalization of bilateral ties. He steadfastly believed that law should serve as the rational bond in great power competition. To this end, he repeatedly advised Chinese leaders to nominate distinguished judges to the International Court of Justice, so that Chinese wisdom might shine on the stage of international law.

At Columbia’s Center for Chinese Legal Studies, Mr. Cohen was a regular presence. We often discussed pressing contemporary legal issues in China. He also took us to academic hubs like New York University. While Western-style academic discussions often took place at standing receptions, he preferred to sit with his Chinese friends at round tables, raising glasses together. As the wine warmed the room, he never failed to introduce young scholars to leading figures from various fields, his eyes gleaming with anticipation: “The future of China and the United States lies in your generation.”

Every moment spent with him has now become a cherished memory:

I once translated my paper, A Constitutional Review of Judicial Interpretations on the Crime of Online Defamation, into English and asked him for comments. Not only did he praise it, he also invited me to collaborate with him, which was eventually published in Foreign Affairs. He invited me to several academic events: at NYU, when commenting on Professor Tong Zhiwei’s exposition of faquanism (theory of right and power), he warmly praised the Chinese character “权” (quan) for its dual meaning of both “right” and “power,” and remarked that unifying the two in one theory was a remarkable intellectual creation. He introduced me to lawyer Tian Wenchang, stressing that as Chinese courts introduced cross-examination procedures, the country would need lawyers skilled in using procedural rules. Speaking of the future of Sino-American relations, he strongly firmly the BIT (Bilateral Investment Treaty) negotiations and earnestly suggested that China strengthen the rule of law and human rights protections to bolster foreign investment confidence.

Mr. Cohen was a true zhongguo tong (China hand). When discussing China's fiscal and tax systems with us, he refuted the narrow view of “only looking at Beijing documents”: “The emperor is far away in the sky; you have to go to the localities to see the real picture.” His words drew laughter from everyone present. But in hindsight, wasn’t this a reflection of his entire scholarly and personal approach—seeing both the forest and the trees, holding the world in mind while caring for ordinary people?

Mr. Cohen also introduced me to his wife, Joan Cohen—a photographer, art historian, and curator who accompanied him on his visits to China where she engaged in deep exchanges with artists from the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Later, at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, she offered a course on contemporary Chinese art history, becoming one of the first to systematically introduce the post-1949 history of Chinese art to the West. I once presented Mr. Cohen with a Suzhou embroidery reproduction of Ou Haonian's masterpiece Joy from Heaven, crafted by master artisan Yao Weijuan. He caressed the persimmons that had seeped color through the silk and the fine threads of spiderweb, he marveled at the craftsmanship. When we met again, he and told me that his wife had loved the embroidery dearly.

Though Mr. Cohen has departed, the aroma of wine around the round tables, the sheen of silk on the embroidery, the group photos in his office, and his oft-repeated words—“The future is in your hands”—will all transform into eternal warmth, illuminating the path for those who follow.

Sun Yuhua

Professor, East China University of Political Science and Law致柯恩先生:一位中美法律界穿针引线的智者

美国东部时间9月22日,柯恩先生永远合上了那双曾为中美法治架桥铺路的眼睛。此刻,纽约求学时的温暖碎片如星子般涌上心头——那个总爱在圆桌酒会上把后辈推到聚光灯下的长者,那个办公室里挂着与周总理合影的学者,那个用毕生精力编织中美理解纽带的智者,就这样悄然谢幕。

犹记得陪老师童之伟教授初访先生办公室时,那帧泛黄的他与周恩来总理的合影格外醒目。先生曾向我讲述,在哈佛工作期间,他便致信基辛格博士,力陈中美建交对世界格局的深远意义。这份超越时代的战略眼光,使他成为推动两国关系正常化的重要力量。他始终坚信,法律应当成为大国博弈的理性纽带,为此多次向中国领导人建言,推荐优秀法官到国际法院,让中国智慧在国际法治舞台上绽放光彩。

在哥大中国法研究中心,柯恩先生是常客,我们经常在一起讨论中国当代的热点法律问题。他还带着我们穿梭于纽约大学等学术重镇。西洋学术讨论常在冷餐会上,不设座位;他偏要与中国朋友围坐圆桌,举杯共话。酒至微醺时,他总不忘将年轻学者引荐给各界精英,眼中闪着期待的光:“中美未来,在你们这代人手里。”

与先生交往的点滴,如今都成了最珍贵的回忆:

我曾将论文《网络诽谤罪司法解释的合宪性审视》译为英文请他斧正。他不仅赞不绝口,更邀我参与他的创作,最终成文发表于《外交事务》杂志。他邀我参与多次学术活动:在纽约大学,他点评我的老师童之伟先生阐释法权说(faquan)说时,盛赞汉语“权(quan)”字兼具“权利”与“权力”的双重智慧,称法权(faquanism)说将两者统一是了不起的创造;他介绍我与田文昌律师见面,强调中国法庭引入交叉询问程序需培养善用程序的律师;谈到中美关系未来,他坚定支持BIT协定,并诚恳建议中国加强法治与人权保障以增强外资信心。

先生是地道的“中国通”。曾与我们论及中国财税制度时,他批驳了“只看北京文件”的片面观点:“天高皇帝远,要到地方走走才知真章。”话音未落,满室皆笑,而今想来,这何尝不是他治学为人的写照——既见森林,又见树木;既怀天下,又念苍生。

柯恩先生还介绍我与他的夫人琼·柯恩相识——这位美国摄影师、艺术史学者、策展人,曾随他访华,与中央美院艺术家深度交流,后来在波士顿美术博物馆学院开设中国当代美术史课程,成为向西方系统介绍49年后中国美术史的先驱。我曾赠先生一幅苏绣大师姚卫娟复刻的欧豪年名作《喜从天降》。他抚摸着画面中浸透绢背的柿子、纤毫毕现的蛛丝,赞叹不已。再见面时,他笑言夫人爱极了这幅绣品。

先生走了,但那些圆桌旁的酒香、绣品上的丝光、办公室里的合影,还有他常说的“未来在你们手里”,都将化作永恒的温暖,照亮后来者的路。

孙煜华 华东政法大学教授

-

In Memory of Professor Cohen

He Jiahong, translated by Heather Han

Professor Jerome A. Cohen was a renowned American scholar of Chinese law. As early as the 1970s, he visited China to gain firsthand insight into its legal system. Over the decades, he remained deeply committed to observing and supporting the evolution of the Chinese legal systems. He developed close ties with China’s legal community, offered constructive suggestions for advancing the rule of law, and made significant contributions to legal exchange between China and the United States.

I had the privilege to meet Professor Cohen on several occasions at academic symposia and similar events. In October 2011, he invited me to teach at the New York University School of Law. During the month-long visit, I taught his graduate-level course on “Chinese Criminal Justice.” In addition, I gave a talk on the“Empirical Study of Miscarriages of Justice in China” to the researchers at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute and a lecture on “Law and Literature” to NYU law students. Professor Cohen also arranged for me to give a keynote presentation on China’s criminal justice reform at a luncheon seminar by the Council on Foreign Relations. Though our views did not always align, I was deeply impressed by his spirit of inclusiveness and understanding during our discussions—hallmarks of a true academic master. He and his wife also graciously invited my wife and me to their home for dinner, where we were warmly received. That visit to New York remains one of my most cherished memories.

I had the privilege to meet Professor Cohen on several occasions at academic symposia and similar events. In October 2011, he invited me to teach at the New York University School of Law. During the month-long visit, I taught his graduate-level course on “Chinese Criminal Justice.” In addition, I gave a talk on the“Empirical Study of Miscarriages of Justice in China” to the researchers at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute and a lecture on “Law and Literature” to NYU law students. Professor Cohen also arranged for me to give a keynote presentation on China’s criminal justice reform at a luncheon seminar by the Council on Foreign Relations. Though our views did not always align, I was deeply impressed by his spirit of inclusiveness and understanding during our discussions—hallmarks of a true academic master. He and his wife also graciously invited my wife and me to their home for dinner, where we were warmly received. That visit to New York remains one of my most cherished memories.

In March 2018, I was invited by the U.S.-Asia Law Institute to attend the National Innocence Network Conference in Memphis, where I gave a keynote address. On my way back to China, I stopped in New York and was again invited by Professor Cohen to engage in academic exchange at NYU School of Law: I first participated in a luncheon seminar chaired by him, during which he “interrogated” me, as he liked to say, on my personal experiences and scholarly work. He then hosted my formal lecture. It was a most enjoyable collaboration—and, as it turned out, our last meeting.

Upon recently learning of Professor Cohen’s passing, I felt compelled to write this brief piece in remembrance of him。

追忆柯恩教授

中国人民大学法学教授 何家弘

柯恩教授是美国著名的中国法专家。早在20世纪70年代初期,他就曾访问中国,了解中国的法律情况。几十年来,他一直关注中国法律制度的发展变化,与中国法学界有广泛交往,为中国法治提出过建设性意见,为中美两国的法学交流做出了重要贡献。

我曾多次在学术研讨会等场合见过柯恩教授。2011年10月,柯恩教授邀请我到纽约大学法学院讲课。在一个月期间,我除了承担柯恩教授给研究生开设的“中国刑事司法”课程教学外,还给亚美法研究所的研究人员做了题为“中国刑事错案实证研究”的讲座,给法学院学生做了题为“法学与文学”的讲座。此外,柯恩教授还安排我到美国“对外关系委员会”的午餐座谈会上做了关于中国刑事司法改革的主题报告。虽然柯恩教授和我的观点并非尽同,但是他在讨论问题时体现的包容和理解,让我领略到学术大师的风范。他还邀请我和妻子到家中共进晚餐,让我们享受了他和夫人的盛情款待。总之,那次纽约之行给我留下了美好的记忆。

2018年3月,我应美亚法研究所的邀请,到孟菲斯市参加美国的“洗冤大会”,并作主题发言。回国途中,我在纽约停留,应柯恩教授邀请到纽约大学法学院进行学术交流。首先,我参加柯恩教授主持的午餐研讨会。柯恩教授按照他喜爱的方式,对我进行“讯问”,内容涉及我的人生经历和学术研究。然后,柯恩教授又主持了我的讲座。那是一次愉快的合作,但也是我们最后一次见面。

近日惊悉柯恩教授逝世,我就撰写了这篇小文,以为纪念。

-

Tribute by Attorney Shi Fumao

Translated by Heather Han

It is with profound sorrow that I learned of the passing of Professor Jerome A. Cohen. For two decades, I had the privilege of knowing this kind and gracious gentleman, whose ever-warm smile and approachable demeanor left a lasting impression. To me, he was not only a titan in the academic realm but also a guiding light that inspired my unwavering commitment to public interest legal service.

Professor Cohen's impact on the development of rule of law in China was both profound and tangible. He was never a distant commentator; rather, he was a dedicated builder who immersed himself in the endeavor. For decades, he steadfastly promoted legal exchange between China and the United States, continuously introducing modern legal principles, pedagogies, and research methodologies to China, which provided invaluable support to the advancement of legal education and the legal profession in the country. He nurtured and influenced generations of Chinese legal scholars, and his academic ideas have imperceptibly become woven into the very fabric of China’s legal development.

In Professor Cohen, we saw the highest ideal to which an American scholar of China could aspire.

His study of China was always grounded in what is called “sympathetic understanding.” His sincere hope was for China to establish a sound and just legal system—an aspiration born of genuine goodwill that earned him respect across borders.

His dedication to nurturing talent transcended the realm of academic exchange. To me, and to countless Chinese legal professionals who benefited from his support, he was a sincere mentor and a true friend. He cared deeply about the growth of younger generations and spared no effort in supporting and uplifting them. His personal integrity and charm lent his influence far greater reach than any written work could achieve.

Though the philosopher is gone, his legacy endures. Professor Jerome Cohen spent his life embodying the essence of a bridge between civilizations and a messenger of friendship. The most meaningful tribute we can offer is to carry forward the spirit of rule of law and the commitment to the public good that he so passionately championed.

Farewell, dear professor. The light of your thought shall never fade.

Attorney Shi Fumao

时福茂律师寄语

惊悉孔杰荣(柯恩)教授与世长辞,悲痛难抑。与先生相识二十载,他一直是那位笑容可掬、和蔼可亲的长者。对我个人而言,他不仅是学术泰斗,更是我矢志不渝投身公益法律服务的引路明灯。

孔杰荣教授对中国法治进程的影响,深远而具体。他不是隔岸观火式的评论者,而是深入其中的建设者。他数十年如一日,致力于中美法学交流,将现代法治理念、法学教育与研究方法源源不断地引入中国,为中国法学教育及律师制度的完善,提供了极为宝贵的智识支持。他培养和影响了几代的中国法学精英,其学术思想潜移默化地渗透于中国法治建设的肌理之中。

孔教授身上,体现了一位研究中国的美国学者所能达到的最高境界。

他研究中国,始终秉持着“同情之理解”。他真正希望中国建立起一套完善、公正的法律体系,这种发自内心的善意,让他赢得了跨越国界的尊重。

他关怀人才培养已超越学术交流。于我,以及于无数受他帮助的中国法律人而言,他是一位真诚的导师和朋友。他关心晚辈的成长,不遗余力地提携后进,这种人格魅力,使其影响力远超学术著作本身。

哲人其萎,风范长存。孔杰荣教授用一生诠释了何为文明的桥梁与友谊的使者。最好的悼念,莫过于将他所倡导的法治精神、公益之心传承下去。

先生千古,思想之光不灭。

时福茂律师

-

Remembering Professor Jerome Cohen.

Xie Pengcheng, translated by Ira Belkin

With the shocking news of the passing of Professor Jerome A. Cohen, the Chinese legal academy lost a true friend and a forthright critic.

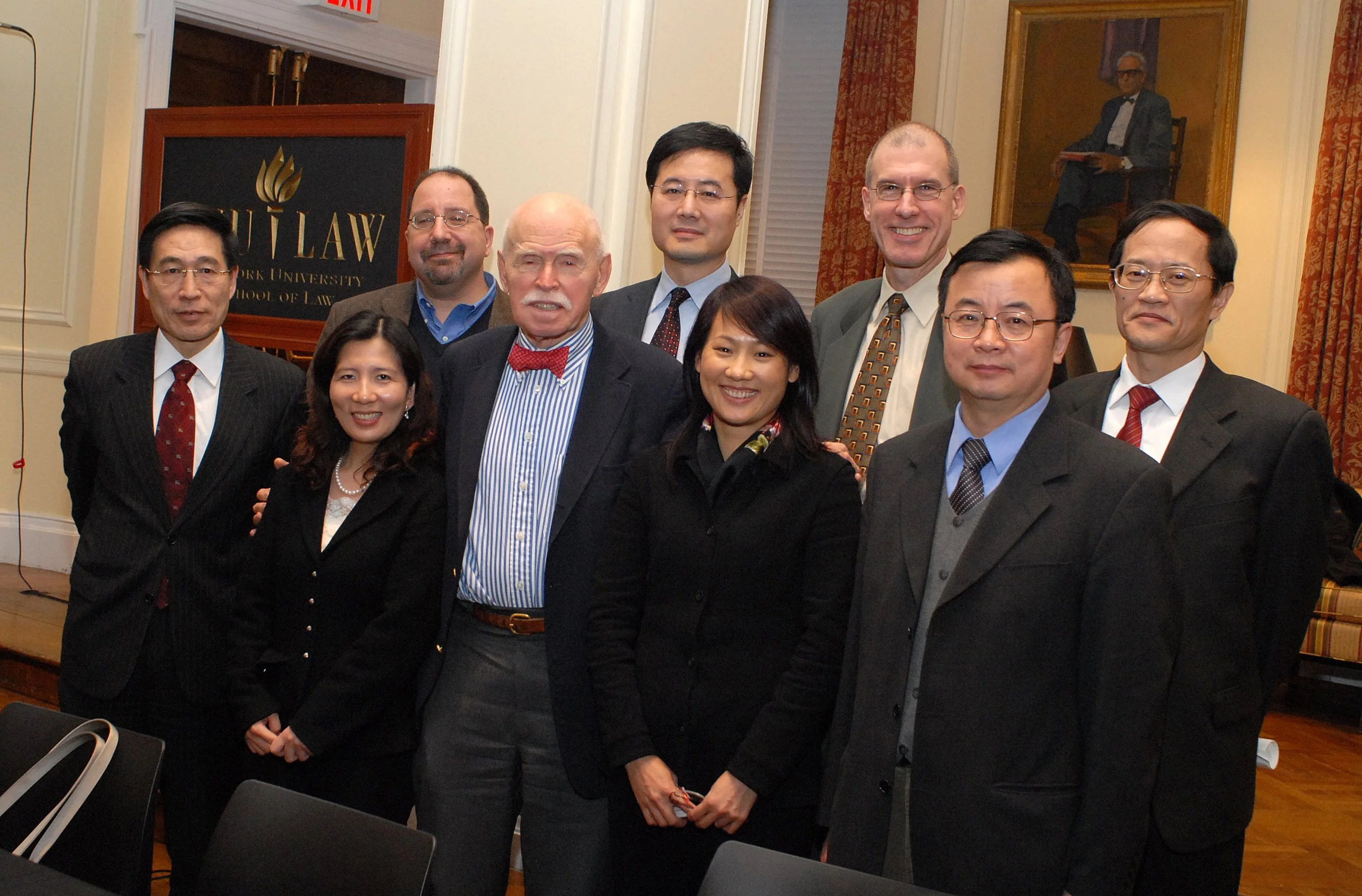

During the 1970’s, at the beginning of the revival of China’s legal system construction, he led the way introducing and explaining American company law, foreign taxation law, and the entire system of international commercial arbitration law. He also persuaded Harvard and New York University’s School of Law to accept the first cohort of Chinese exchange students, which included eight members of the “class of ‘79” (China’s first class of law graduates after the Cultural Revolution). They became future vice presidents of the Supreme People’s Court, distinguished international arbitrators and university presidents. In other words, they became the cohort that presented itself as the face of the Chinese legal community to the world.

Professor Cohen firmly believed that “the law is not only what is written in the text of statutes, but it is also in the way people implement the law in practice.” He often travelled between the United States and China making concrete suggestions for statutory changes in the areas of death penalty review, criminal procedure reform and the regulation of the legal profession. He also helped Chinese companies to invest overseas and American companies negotiating to open factories in China. He brought legal reform to the field of the Chinese economy’s “reform and opening up.”

Even more worthy of emulation is his position on learning: he had an insider’s understanding and appreciation for China, and an outsider’s sharp analysis of issues, a willingness to dare to criticize and a pleasure in welcoming criticism. In the final analysis, he allowed the law and the facts to speak for themselves.

Today, as U.S.-China relations have once again entered a period of confusion, Professor Cohen’s legacy is not just his deep knowledge of Chinese criminal procedure law and the transitional nature of China’s legal system, but his standard of what it means to be a scholar: first, respect others; promote dialogue; begin by putting yourself in the dialogue. I hope that future scholars can use this standard and allow scholarly exchanges to serve to promote justice and respect between our two countries

Xie Pengcheng, former Director of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate Center for Research and Theory, Professor and Lecturer, Shandong University悼念孔杰荣教授

惊悉孔杰荣(Jerome A. Cohen)教授仙逝,中国法学界失去了一位真挚的朋友与严谨的诤友。上世纪七十年代末,中国法治重建方启,是他率先把美国公司法、涉外税法、国际商事仲裁整套制度译介来华,更说服哈佛、纽约大学招收首批中国法学留学生;八位“七九级”学生后来成为最高人民法院副院长、知名仲裁员、高校校长,中国法走向世界的第一张名片由此写就。孔教授坚信“法治不仅是条文,更是人的实践”,他常年往返中美,为死刑复核、刑诉法修改、律师制度重建提供具体条文建议,也为中国企业赴美投资、美企来华设厂谈判,把法律嵌入改革开放的经济叙事。更值得效仿的是他的治学立场:既以“内部人”的同情理解中国,又以“外部人”的锋利审视问题,敢于批评也乐于被批评,始终让事实与法律本身说话。今天,当中美关系再度走入迷雾,孔杰荣留下的不只是厚重的《中国刑事司法》与《转型中的中国法》,更是一把标尺——研究他者,先尊重他者;推动对话,先把自己放进对话。愿后来者循此标尺,让学术真正服务于两国人民的正义与尊严。

最高人民检察院检察理论研究所原所长、山东大学讲席教授 谢鹏程

-

In warm remembrance of Professor Jerome A. Cohen

He Weifang, translated by Ira Belkin

About six months ago, my friend, lawyer Tao Jingzhou, told me he had just been to New York City and had paid a visit to Professor Jerome Cohen at his home. Jerry’s mind was clear but he was unsteady on his feet . He even told me Jerry had asked about my situation and asked TAO to give me his regards.

On September 24, in Beijing, I saw a post from Professor Donald Clarke on the China Collection website with the shocking news that Professor Jerome Cohen had passed away. Even though he was 95 years old, when I heard the news he had passed, I felt an unbearable sadness.

I understand that most people will recognize what a great loss this outstanding scholar’s passing will be for China’s legal academy and China’s project to establish the rule of law.

I immediately posted the news in my WeChat friend group: “he is the founder of modern Chinese legal studies in the West, a longtime leader in the scholarly field, a tireless participant and advocate for China’s rule of law work, a passionate matchmaker in U. S. -China exchanges, a wise and benevolent elder and friend. May he rest in peace.”

I added a photo we took at an October 13, 2019 conference on 40 years of Chinese legal reform at the University of Michigan. Very quickly thereafter, many people left messages of condolences.

Over the past 30 years, I have been very proud to have had many opportunities to meet Jerry and seek his advice. I have also learned a great deal from reading his written works.

In 1996, I accepted the invitation of Harvard University Law School Professor Bill Alford and a fellowship from the Committee on U.S. -China Scholarly Exchanges. After I became a visiting scholar at EALS, I was grateful to Jerry for his foresight and contributions in creating this organization.

Because I participated in China’s legal reform at a deep level, some of my written work met with Jerry’s interest and approval. For example, after I published my 2008 blunt criticism of Chinese leaders’ “Three Supremes” policy, Jerry very quickly published an essay that included praise and encouragement.

At a conference to discuss my 2012 book, In the Name of Justice: Striving for the Rule of Law in China, published by the Brookings Institute,

Jerry travelled to D.C. to join me, Bill Alford, Paul Gewirtz and Jon Huntsman, the U.S. Ambassador to China at the time. Jerry’s comments emphasizing the political obstacles faced by rule of law advocates in China left a deep impression upon me.

Jerry was the same age as his colleague, Jiang Ping, who passed away in 2013. When Jiang Ping passed away, Jerry called me to express his condolences. Now Jerry has left us as well. For these two gentlemen who did so much to establish the rule of law in China, one could say that their lofty ambitions have gone unfulfilled, they died without achieving their goals. This makes one feel especially sad and unwilling to accept defeat.

The mission our elders failed to complete needs those who followed them to continue their efforts. All that Professors Cohen and Jiang Ping endured proves that establishing the rule of law in China is an arduous task. Fortunately, they gave us a good foundation, showed us how to be role models, and provided us with a guiding light that can never be extinguished.

HE Weifang

深切悼念Professor Jerome A. Cohen

贺卫方(北京大学法学教授)

大约半年前,我的朋友陶景洲律师告诉我他刚刚访问纽约,专程到Professor Jerome Cohen家中拜访了他,陶先生告诉我Jerry头脑很清楚,只是行走已经不便,还告诉我Jerry专门问起我的情况,特别让陶先生转达对我的问候。北京时间9月24日,我在一个名为The China Collection的网站上读到Donald Clarke教授的一篇贴文,惊悉Jerome Cohen教授逝世的消息,虽然他已经95岁高龄了,但听到噩耗还是难忍心中的悲痛。了解这位杰出学者的人们都会意识到,他的离去对于中国法学界和中国法治事业是多么重大的损失。我立即在自己的微信朋友圈里报告了这一消息:“他是西方世界研究中国现代法律的奠基者和长时期的学术领袖,是中国法治事业不懈的参与者和推动者,是中美法学交流的热情冰人,是智慧而仁厚的长者和朋友。愿他安息!”末尾附上了2019年10月13日在Michigan University中国法治40年学术研讨会上我为他拍的一张照片,很快就有很多有人留言,表达他们的哀悼。

过去三十多年的时间里,我很荣幸有很多机会与Jerry见面并请益,通过阅读他的著述得到很多启发。承蒙哈佛法学院Bill Alford教授邀请和美中学术委员会的资助,1996年我得到在哈佛EALS做访问学者的机会,感受到Jerry创建的这个学术机构的远见和巨大贡献。因为深度参与了中国的司法改革,我的一些作为也自然得到了他的关注和鼓励。我的一些文章,例如2008年对于中国领导人提出的“三个至上”的直率批评,他很快就发表文章表达赞同和鼓励。2012年Brookings Institution Press出版了我的文集In the Name of Justice: Striving for the Rule of Law in China, Jerry专程赶到DC参加Brookings组织的讨论会,和Bill Alford,Paul Gewirtz教授以及前驻华大使Jon Huntsman先生同台研讨,Jerry对于中国法治遭遇到的政治阻碍的强调令人印象至深。

Jerry的同龄人和同行老友江平先生于2023年12月逝世,Jerry曾专门致电表达悼念;如今Jerry也离开了我们。对于这两位中国法治大厦的建设者而言,他们都可谓壮志未酬,赍志而殁,这是特别令人痛心和不甘的。前人未竟的事业需要后人继承,Cohen教授和江平教授所经历的种种也证明了在中国建设法治是多么艰巨的工程,好在他们给我们奠定了基础,树立了榜样,更是我们跋涉路途上的两盏永不熄灭的明灯。

-

Tribute to Jerome Cohen

It was my great fortune to have met Jerry in the early years of my career. He was my teacher in the seminar "Doing Business with China" at Harvard Law School in 1985. The seminar was conducted at irregular hours because he was actively engaged in doing business with China, flying between the US and China on a weekly basis. I recall marveling at his boundless energy and the many fascinating stories he shared with the class. I also remember his constructive advice that I would need to expand my sentences in writing—guidance that served me well throughout my career.

I was practicing at a New York law firm when Jerry joined the faculty of NYU Law School in the early 1990s. Soon thereafter, Jerry invited me to present at a symposium on "Asia in the Twenty-First Century" at NYU, which led to my first English publication in the NYU Journal of International Law & Politics. In 1994, while I was clerking at the US Court of International Trade, Jerry invited me to co-teach a course on "International Law: East and West" at NYU. Although Jerry did most of the work, he generously gave me credit for co-teaching. Looking back, Jerry's efforts in those early years were critical in helping me launch an academic career in the United States.

Jerome Cohen was a giant in the field and a great mentor and friend. His passing marks the end of an era. May his memory be a blessing!

Julia Ya Qin

Professor of Law

Wayne State University Law School -

In Memory of Professor Jerome A. Cohen

Bing Ling

(The Chinese version is to be published in Ming Pao Daily in Hong Kong on 4 October 2025. Translation by Bing Ling with aid of ChatGPT)

Professor Jerome A. Cohen of New York University, the renowned scholar of Chinese law, passed away last week at the age of ninety-five. Throughout his life, Professor Cohen dedicated himself to the teaching, research, and practice of Chinese law, nurturing generations of students across the world. His influence on the development of China’s contemporary legal system and his contributions to the cultivation of Chinese and international legal talent place him among the foremost Western scholars of the past century.

A distinctive feature of Professor Cohen’s scholarship on Chinese law lay in his profound command of international law. He consistently grounded his arguments in international legal principles, thereby enhancing the authority and persuasiveness of his work. His early landmark publication, People’s China and International Law: A Documentary Study, co-authored with Professor Hungdah Chiu of Taiwan, remains unsurpassed in its comprehensive account of China’s practice on international law. Motivated by his belief in the rule of law in international relations and in China’s proper role within the global order, he worked tirelessly to encourage China’s engagement with the international community. At the same time, he was forthright in his criticism of China’s foreign policy missteps and violations of international law, offering candid and principled counsel.

When China became embroiled in the South China Sea arbitration a decade ago, he sharply criticized China’s refusal to cooperate with the tribunal, underscoring the binding legal force of the arbitral award and advocating that China and the Philippines use the arbitral award as a basis for negotiation and conflict resolution. Similarly, regarding the Sino-Japanese dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, he urged that international law serve as the framework for dialogue and recommended recourse to the International Court of Justice as a means to resolve the conflict peacefully.

The passing of Professor Cohen marks the end of an era. Among the elder generation of overseas scholars on China, with Professor Cohen as their exemplar, there was a rare clarity of vision concerning the institutional and cultural differences between China and the West, coupled with an unwavering belief in the goodness of human nature, the trajectory of social progress, and the benefits of international cooperation. In recent years, however, surging tides of nationalism worldwide, and the entrenchment of zero-sum thinking about geopolitics and national security among both policymakers and academics in China and the United States, have all but extinguished the faith and wisdom of that earlier generation. The future of relations between great powers thus appears deeply uncertain.

[Original Chinese version]

追思孔傑榮教授

凌兵 法律學人@hk

紐約大學著名中國法學者孔傑榮(Jerome A. Cohen)教授上週逝世,享年95歲。孔教授畢生致力中國法律的教學、研究與實踐,桃李遍天下。其對中國當代法制演進之影響,對中外數代法律人才培育之貢獻,在近百年西方學者中,堪稱翹楚。

孔教授在中國法領域的建樹,一大特色在其對國際法制度的深刻瞭解,每以國際法原則為立論根基,使其論述更具權威與說服力。他早年成名作為與台灣丘宏達教授合著之《人民中國與國際法》(People’s China and International Law: A Documentary Study)一書,兩卷巨著,對中國國際法實踐之陳述,至今無出其右。基於對國際法治及中國國際地位的信念,他推動中國對外開放,加入國際體系,可謂不遺餘力;而對中國外交失當,有違國際法之作為,亦率直批評,坦誠建言。十年前中國捲入南海仲裁案,他對中國與法庭不合作的態度,嚴加批判,強調仲裁裁決之法律效力,主張中菲兩國在仲裁基礎上以談判消弭紛爭。對於中日釣魚島爭端,他亦主張以國際法為談判基礎,建議兩國藉助國際法院訴訟,和平解決爭端。

孔傑榮教授辭世,象徵一個時代的終結。海外中國研究的老一輩學者,以孔教授為代表,雖對中西社會制度與文化差異明察秋毫,惟對民心之良善、社會進步之趨勢及國際合作之裨益,抱持堅定信念。近年來世界范圍內民族主義惡浪洶湧,中美兩國從政界到學者,凡事皆以地緣角力與國家安全的零和思維為依歸,老一代學者的信仰與智慧喪失殆盡。大國關係的未來,令人堪憂。

-

It is hard to imagine the field of Chinese law without Jerry. He bestrode it like a Colossus. I first saw his name when I came across his book, The Criminal Process in the People’s Republic of China, in the Canadian Embassy library in Beijing in the spring of 1978 when I was a student there. It fascinated me immediately, and inspired by it I wrote my first long-form essay in Chinese, entitled “也谈《加强法制》” (“On ‘Strengthening the Legal System’”) at Nanjing University a year later.

I arranged to meet him in the spring of 1980 in Tokyo when I was living there and he was passing through. I remember—or at least think I remember—asking him whether he thought there was a future in the Chinese law field. What a question to ask Jerry! You can readily imagine the answer and the compelling way in which it was delivered. A few years later I was in law school, taking his course in Doing Business in China.

Those early meetings were life-changing events for me, and ever since that time he was mentor, teacher, cheerleader, and friend.

On social media and on email listservs, many have commented on how much he did for them and others. But the meaning of his life extends beyond that—it includes the inspiration he provided to others to emulate his model of generosity and thereby to enrich the lives of still others, in an ever-widening ripple. Many people probably don’t even know that they owe the guidance and mentoring they received from someone to that someone’s just trying to follow the example Jerry set in their own case. Jerry lives on in a very real way in the people and institutions he fostered over the years.

To repeat what many have already observed: Jerry was a real mensch. May his memory be a blessing.

-

I had the great fortune of being within Jerry’s orbit for five years. On the second day after my arrival in New York, he invited me to lunch with him and Joan at their home on Park Avenue, providing detailed step-by-step instructions on how to get there. I arrived bearing a gift—Chinese tea, of course—and felt a bit embarrassed months later when I overheard Joan tell Jerry, “Could you ask people to stop bringing tea?” Jerry was amused.

Last year, when I asked him for a blurb for my book while he was already quite ill, he responded immediately and with augmented enthusiasm. Like so many others, the world is a stranger place without Jerry. His generosity, uplifting spirit, attentive care for junior scholars, and his wit and humor will forever be remembered by so many.

Ling Li

University of Vienna

-

In the summer of 2006, Jerry Cohen visited Beijing, and I invited about 15 lawyers to join him for dinner. Gao Zhisheng was among them, and we all sensed that he was already on the road to prison. Jerry advised Gao to slow down, as we discussed strategies for the Rights Defense (Weiquan) Movement then in its early stage. Jerry had already given immense support to the blind activist Chen Guangcheng and in the case of Sun Zhigang—an incident later seen as the symbolic beginning of the Weiquan movement. He warmly praised the efforts by Xu Zhiyong, myself, and others who tried to use existing legal channels to promote the rule of law in China. For decades, he poured tremendous passion into supporting Chinese human rights defenders. Every time we met, he asked me about the latest situation of Chinese lawyers and prisoners of conscience.

Even before I was born, Jerry had begun studying Chinese law and politics. Later, he played a decisive role in reviving legal institutions from the ashes of the Cultural Revolution and Mao-era lawlessness. He was the godfather of the study of PRC law in the West—a mentor of mentors. No one did more than Jerry to advance Sino-US exchanges in legal education and the legal profession. When I co-initiated “Chinese Human Rights Lawyers Day” in 2016, I persuaded the other organizers to establish the Award for Advancing Rule of Law and Human Rights in China and to present the inaugural honor to Jerry. This award was cancelled in the following year, so Jerry’s became the only one.