By Qin (Sky) Ma

Free speech in China faces growing restrictions. The government’s push for social stability often means tight control over public discourse. Legal scholars find themselves in a tough spot: they aim to be critical thinkers but must be careful about dissenting openly. Most scholars avoid publicly criticizing official policies. However, the legal community’s response to the feared shutdown of the China Judgments Online (CJO) (中国裁判文书网) at the end of 2023 was a noteworthy deviation from the norm, revealing the complex dynamics between legal scholars and state authority in China. This essay analyzes how Chinese legal scholars reacted to the CJO incident and the judiciary’s subsequent reaction, illuminating the strategies intellectuals use to critique within limited spaces.

The CJO Incident

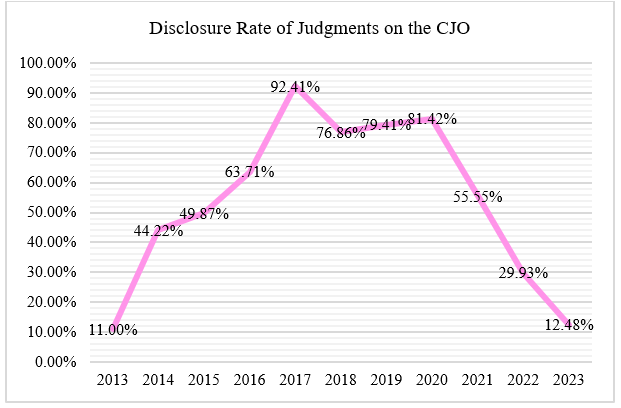

Since its launch in 2013, the CJO website has significantly improved judicial transparency by publishing hundreds of millions of court judgments online. It has helped lawyers, scholars, and the public understand court actions and is vital for empirical legal research. However, beginning in 2020, observers noticed a “cliff-shaped decline (断崖式下跌)” in the number of published judgments as well as retroactive deletion of documents, raising concerns about decreasing transparency. A substantial number of administrative cases were not uploaded. The selective disclosure suggested a strategic effort by the courts to manage public perception.

Note: The disclosure rate equals the number of cases decided by courts each year, based on the SPC’s work reports (2014-2024), divided by the number of judgments from the same year posted on the CJO, according to the website’s own count as of June 4, 2024. If duplicate posts and blank posts are removed from the count, the actual disclosure rate may be lower.

In late November 2023, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) indicated through an internal notice its plan to establish a new database for courts’ internal use called the National Court Judgments Archive (全国法院裁判文书库). Initially, this information was not known to the public. However, in early December, a purportedly leaked red-headed document from the SPC General Office was widely circulated on social media. This document revealed the internal database plan and sparked significant public debate.

Many people wondered if the new archive meant the end of the CJO. Leading Chinese legal scholars and lawyers began speaking out online and offline in support of the CJO, including He Haibo, Lao Dongyan, and Zhou Guangquan of Tsinghua University Law School, Fu Yulin and Che Hao of Peking University, Wu Hongyao of China University of Political Science and Law, Han Xu of Sichuan University, and Wang Jiangyu of City University of Hong Kong, among others. They wrote articles, posted on Weibo and WeChat, held seminars, and engaged in other forms of advocacy to highlight the importance of maintaining the CJO for judicial transparency, legality, rationality, and rule of law principles. They argued that shutting down the database would conflict with the SPC’s own guidelines issued in 2013 and 2016. They also discussed problems plaguing the CJO including data gaps, low upload rates of documents, delayed uploads, and uneven regional distribution. Most scholars strove for a constructive tone in their advocacy and emphasized supporting rather than outright criticizing the judiciary.

In their efforts to “rescue” the CJO, legal scholars found an opportunity—or perhaps a necessity—to voice their concerns about declining judicial transparency openly and critically. Their public outcry was remarkable not only for what was said but also for the fact that the scholars spoke out at all, revealing the normally hidden tensions between the state-controlled public discourse and the legal community.

Judicial Response

Eventually, in late December, the SPC issued an announcement to clarify that they never planned to shut down the CJO. It introduced a plan to create multiple databases - dubbed “Two Archives, One Website (两库一网)” – in order to foster judicial transparency in a more structured way. In additional to the new, internal-only National Court Judgments Archive, it planned to add a People’s Courts Case Archive (人民法院案例库), featuring cases of reference value accessible by the public as well as judges. The SPC emphasized that the CJO and the two archives “complement and enhance each other, and it is not a matter of replacing the network with the repository or opening one at the expense of closing the other.” Further, at the National Conference of High Court Presidents on January 14, 2024, the SPC emphasized the importance of publishing court judgments online.

It suggests that the space for critical discourse, though constrained, is not entirely closed and that strategic engagement by scholars can have impact.

With that, the CJO rescue operation appeared to have achieved success, as the SPC publicly acknowledged the value of the CJO and declared its commitment to furthering judicial transparency. However, CJO supporters remain concerned that even if the website is not entirely shut down, its offerings remain selective. On January 13, 2024, media outlets reported that Zhejiang Province’s court system had been directed by its leadership to increase the number of judgments uploaded to the CJO. However, the report also noted that judges in several major provinces, including Sichuan, Chongqing, Tianjin, Hainan, and Guangdong, had not received similar directives. This raises questions about the central authorities’ commitment to maintaining a consistent level of transparency nationwide.

Notably, the SPC’s response to the legal scholars in the CJO incident marked a departure from the authorities’ usual narrative of silence and suppression. By engaging with the criticisms and providing clarification, the court demonstrated an unusual willingness to communicate with the legal community and be held accountable.

Where does the CJO incident leave legal scholarship in China? It suggests that the space for critical discourse, though constrained, is not entirely closed and that strategic engagement by scholars can have impact. Ideally, the incident could serve as a precedent for future interactions between legal academia and the judiciary. More responsiveness from the SPC could serve as the foundation for consensus-building and greater scholarly and public oversight. The future of free speech in China will depend on the continued ability of intellectuals to navigate the limited avenues for critical discourse, pushing the boundaries while managing the risks. Recognizing the progress made, albeit with skepticism, is essential for understanding and influencing this evolving dialogue.

* * *

Qin Ma is a 2023-2024 Hauser postdoctoral global fellow at NYU School of Law and incoming 2024-2025 Max Weber fellow in the European University Institute Department of Law.

Suggested Citation:

Qin (Sky) Ma, “Legal Dialogue, Chinese Style,” USALI Perspectives, 4, No. 9, June 6, 2024, https://usali.org/usali-perspectives-blog/legal-dialogue-chinese-style.

The views expressed in USALI Perspectives essays are those of the authors, and do not represent those of USALI or NYU.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.