Download the PDF

By Yizhi Huang**

Abstract: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development identifies ensuring equal access to justice for all as one of its specific goals, aligning with the rights proclaimed in multiple international human rights treaties. Taking “equal access to justice” as an entry point, this article compares the 2030 Agenda and international human rights treaties across three dimensions: background, content framework, and monitoring mechanisms. This study finds that the concept of obtaining justice through courts (judicial justice) differs in the two frameworks: human rights treaties encompass rights throughout all stages of judicial proceedings, whereas the 2030 Agenda focuses primarily on equal access to judicial processes. Moreover, their monitoring methods differ: human rights treaties rely on expert committees that periodically review state reports and issue recommendations, while the 2030 Agenda uses an indicator system to assess global trends, but this system faces challenges in using quantitative data to measure judicial justice. Finally, this article analyzes the strengths and limitations of promoting judicial justice through the sustainable development framework. It argues that it is necessary to integrate the human rights mechanisms with the 2030 Agenda and coordinate both approaches in order to enhance judicial protection for vulnerable groups and achieve judicial justice for all.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the Anti-Discrimination Law Review [反歧视评论], No. 12, 2025 under the title 所有人的正义:以发展和人权测量司法保护, and translated into English by the U.S.-Asia Law Institute. The institute thanks the author and publisher for permission to publish it in English.

***

At the 2015 United Nations Summit on Sustainable Development, all member states unanimously adopted Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by 2030 (hereinafter referred to as the 2030 Agenda), which encompasses 17 goals and 169 specific targets across economic, social, and environmental dimensions, and made a commitment to “leave no one behind.”[1] This ambitious set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represents an advanced version of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), offering new pathways and opportunities to bridge the gap between countries regarding human rights and development. Although not framed explicitly within a human rights paradigm, many of the SDGs reflect core elements of international human rights treaties concerning economic, social, and cultural rights. What gives the SDGs their transformative potential is Goal 16 (SDG 16) on “peace, justice, and strong institutions,” which aims to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.” This goal covers several key aspects of civil and political rights, such as personal security, judicial remedies, and fundamental freedoms. It signals a shift in the international community’s understanding of how to evaluate development, from focusing on outcomes to emphasizing the intrinsic elements of development such as the rule of law and obtaining justice through courts (judicial justice). But is it feasible to assess the rule of law and justice through a development framework? Specifically, in terms of “access to justice for all,” how does it compare to the international human rights mechanisms in protecting the rights of vulnerable groups? And can the two approaches work together to promote judicial justice?

In the 2030 Agenda, “access to justice for all” as the core element of SDG 16 is further articulated in target SDG 16.3: “Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all.” This is also one of the fundamental rights enshrined in multiple international human rights treaties and is closely linked to the realization of other economic, social, and cultural rights. This article uses “equal access to justice” as an entry point to explore how development and human rights frameworks can be jointly leveraged to promote equal judicial protection for vulnerable groups. Although both the 2030 Agenda and international human rights treaties fall under the United Nations system, they emerged through different processes and reflect varying degrees of consensus or agreement among countries. While the two share overlapping content, they differ in the way similar issues are articulated, as well as their implementation and monitoring mechanisms; their binding force on states also exhibits notable differences. Therefore, this article compares the 2030 Agenda and international human rights treaties with regard to equal access to justice from three dimensions: 1) origins and context, including the formation and nature of both frameworks, how equal access to justice is positioned within each system, and its relationship to other goals or rights; 2) content framework, including how this issue is formulated in the texts, the evolution or interpretive expansion of the content, and the relationship between the two frameworks; 3) implementation and monitoring mechanisms at both the national and global levels, as well as the role of civil society participation. Following this three-part comparison, the article will examine the strengths and limitations of using the development framework to advance judicial justice from a human rights perspective. It will then explore the possibilities of integrating human rights and development approaches to enhance access to justice for vulnerable groups.

I. The Intersection of Development Frameworks and Human Rights Mechanisms

International human rights treaties and the 2030 Agenda are important mechanisms that fall under the United Nations’' two main pillars: human rights and development. Although both are resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly (UNGA), they differ considerably in how they were formed and in their legal nature. The term “international human rights treaties” refers to a body of human rights conventions that emerged gradually from the 1960s, based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the UNGA in 1948. The nine most important of these conventions are commonly referred to as the “core international human rights treaties.”[2] While the UDHR itself does not have direct legal binding force, it catalyzed the adoption of many legally binding international human rights instruments. Once a country ratifies one of these treaties, it becomes legally binding on that country. By contrast, the 2030 Agenda is not a legally binding instrument, but it was unanimously adopted by UN member states, reflecting the broadest possible international consensus. This 2015 resolution is built on decades of UN work in sustainable development[3], and establishes goals across economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Covering nearly every aspect of national governance, it serves as a comprehensive guiding framework for global and national development actions and has had significant global influence.

As the MDGs approached their 2015 deadline, the UN initiated the development of a more comprehensive sustainable development agenda. This was partly in response to gaps identified during MDG implementation, especially the absence of the rule of law and human rights considerations.[4] Among the goals of the new agenda, SDG 16 on “peace, justice, and strong institutions” was the most debated and contested part of the discussions. It was only after extensive lobbying and negotiations that it was included among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. This outcome was the result of years of political, strategic, and academic efforts by human rights advocates, practitioners, and researchers.[5] During the process of formulating this development framework, the UN actively sought input from a wide range of stakeholders, especially from the most marginalized populations. Across these groups, the lack of legal protection and judicial remedies emerged as a shared concern. Various UN agencies and international/regional organizations proposed recommendations based on existing international human rights standards, advocating for the inclusion of “justice” as an independent goal. At the same time, recognizing the profound impact of conflict and violence on development, some countries and organizations also lobbied for the inclusion of judicial justice in the new agenda.[6] The underlying consensus behind these efforts was that peace and development depend on building an inclusive society that respects the rule of law and human rights. In this way, SDG 16 serves as both a goal in itself and a supporting framework that enables the realization of all other development objectives.

The “radical” potential inherent in SDG 16 expands the paradigm of development.[7] By incorporating SDG 16, the 2030 Agenda strengthens the link between development and human rights and integrates “justice” throughout all 17 goals. In order to achieve this transformative goal, 12 specific targets have been established under SDG 16, including two related means of implementation targets and ten outcome targets. The ten outcome targets broadly fall into three categories: 1) mitigating threats to justice, including curbing corruption, violence, and torture, and combating corruption and organized crime; 2) establishing effective mechanisms, covering aspects such as representation, coverage of all levels, participation, and cooperation; 3) safeguarding fundamental freedoms, such as access to legal identity and various forms of information. SDG 16.3 on “equal access to justice for all” is connected to all three categories and serves as a safeguard for achieving the other targets, making it a core element. SDG 16.3 is also closely linked to other SDGs: without guarantees of access to justice, goals like poverty eradication, inequality reduction, and other development goals cannot be fully achieved. That being said, the greatest challenge in implementing SDG 16.3 may lie in defining and measuring “equal access to justice for all.”

The 2030 Agenda is explicitly based on international human rights treaties, and equal access to legal protection is a core component of these treaties. In most international human rights instruments, equal access to justice is not set out as a standalone right but is articulated under the broader principle of equality before the law. This principle is expressed in Article 7 of the UDHR[8]and Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[9], both of which affirm that all individuals are entitled to equal protection of the law. Both the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) emphasize equality before the law and the equal opportunity and assistance required to exercise such legal status. The 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) includes a dedicated provision on access to justice. The emphasis on this right is closely linked to movements since the 1970s that advocated for the establishment of state institutions to safeguard citizens’ right to litigation.[10] As human rights and the rule of law have become global norms, this right has been increasingly discussed. Its scope and substance have been further developed through the implementation of human rights treaties, and it is now widely regarded as “a basic human right as well as an indispensable means to combat poverty, prevent and resolve conflicts.” [11] This right is especially crucial for vulnerable groups, because it serves as a pathway to and guarantee for the realization of other rights.[12] It is worth noting that “Access to Justice” is translated as “诉诸司法” (appeal to justice) in the Chinese version of the 2030 Agenda, whereas in human rights treaties it is rendered as “获得司法保护” (obtain judicial protection). Does this suggest a divergence in the interpretation of judicial justice under the two frameworks? The next section of this paper will first examine how this right is articulated in international human rights treaties and analyze the elements it encompasses, and then use the analysis as a basis for distinguishing various expressions of this goal and relevant indicators under the sustainable development framework.

II. Justice under Different Frameworks

(1) Equal Access to Justice under the Human Rights Framework[13]

As previously mentioned, multiple core international human rights treaties require states to take measures to ensure that different groups enjoy equal opportunities and receive assistance in achieving legal equality. This includes equal access to judicial procedures, equal treatment at all stages before courts and other adjudicative bodies, and the right to fair compensation or damages. The most recent of these treaties, CRPD,which was adopted in 2006—contains more detailed provisions in this regard. It emphasizes that legal personality [of disabled people] must be recognized and that existing disability barriers should not be viewed as a lack of legal capacity. Rather, states should adopt measures to provide accommodations that enable persons with disabilities to exercise legal capacity on an equal basis. Building on this, the CRPD includes a dedicated article on access to justice, requiring states parties to “ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others, including through the provision of procedural and age-appropriate accommodations, in order to facilitate their effective role as direct and indirect participants, including as witnesses, in all legal proceedings, including at investigative and other preliminary stages.”[14] The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) adopts a slightly different wording but also stresses that children should be treated in a manner appropriate to their evolving capacities (determined by age and maturity), including the right to express their views directly or through a representative in judicial or administrative proceedings.

Each of the core international human rights treaties is monitored by a committee, also known as a treaty body composed of independent experts with expertise in human rights. These committees have the authority to issue general recommendation or comments that offer evolving interpretations of treaty provisions to guide states parties in fulfilling their obligations. For example, in its 2005 General Recommendation,[15] the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD Committee) issued guidance on how to prevent racial discrimination in the functioning of criminal justice systems. This included the rights of defendants, the duties of states, and the status and support to which victims are entitled during criminal proceedings. In its 2012 General Comment,[16] the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) provided specific guidance on ensuring that persons with disabilities can file complaints and testify in legal proceedings. Its recommendations include “recognition of diverse communication methods, allowing video testimony in certain situations…, providing professional sign language interpretation” and other forms of assistance. In 2015, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee) issued a comprehensive General Recommendation No. 33 on Women’s Access to Justice.[17] This document underscored that women’s access to justice is critical for realizing all the rights protected under CEDAW. It analyzed the systemic barriers women face in seeking justice, identified problems within current legal systems and practices, and offered recommendations to states parties across different legal fields and procedures. It emphasized that ensuring women’s access to judicial remedies requires six interrelated core elements: justiciability, availability, accessibility, good quality, provision of remedies to victims, and accountability of justice systems. In 2019, the Committee on the Rights of the Child[18] issued a General Comment listing the “core elements of a comprehensive child justice policy,” covering every stage from prevention to intervention and adjudication. It emphasized that judicial processes should enable children to participate in the child justice processes under conditions of equality, with legal assistance,” and ensure that children do not face discrimination throughout the process. It also outlined proactive remedial measures that should be taken.

Through both treaty provisions and general recommendations/comments, it is evident that the human rights framework conceives of equal access to justice in broad terms. It encompasses the opportunity to have one’s disputes heard by judicial bodies, the right to fair treatment at every stage of the process, and the right to legal aid or other forms of support. While treaty bodies have traditionally placed emphasis on the rights of defendants in criminal justice, they have also increasingly paid attention to the rights of victims. In its general recommendations, for example, the CEDAW Committee interprets access to justice as applying to all areas of law, including constitutional, criminal, civil, family, and administrative law. These treaty bodies call on states parties to actively remove barriers, provide reasonable accommodations, and offer effective support, including legal aid and procedural arrangements. Each committee also tailors its recommendations to address the unique barriers faced by specific groups. This allows them to respond to diverse legal needs in order to promote equal access to justice for all.

(2) Equal Access to Justice under the Development Framework[19]

The 2030 Agenda places the principles of equality and non-discrimination at its core, committing to “leave no one behind” and to “endeavor to reach the furthest behind first.” These commitments reflect a clear focus on vulnerable and marginalized groups. SDG 16.3 emphasizes ensuring equal access to justice for all. Given the disadvantaged position of vulnerable groups in this area, the emphasis naturally falls on promoting the right of the most marginalized to access the justice system and obtain remedies. This objective is consistent with that of international human rights treaties. However, the 2030 Agenda differs significantly from human rights treaties in terms of how this right is articulated and what it encompasses. SDG 16.3 states upfront that it aims to ensure “equal access to justice for all.” Unlike human rights treaties, which often contain separate provisions for specific groups, this formulation uses the broader term “for all,” thereby covering a wider population. As a result, SDG 16.3 sounds more like a general slogan or declaration. It lacks the detailed articulation of rights related to equal access to justice that can be found in human rights instruments. This raises the question: What standard does this specific target set for countries?

Unlike the legal provisions and interpretative frameworks established by treaties, the 2030 Agenda uses a combination of goals, targets, and indicators to define its objectives and assess progress. While formulating the goals and targets, the United Nations also solicited input on how to develop indicators to measure them. In March 2015, the United Nations Statistical Commission established internal bodies and an Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDGs) [20] tasked with developing a global indicator framework for the SDGs. In June 2015, the IAEG-SDGs released the indicator development proposals it had received.

For SDG 16.3, two indicator proposals were put forward: First, “Proportion of those who have experienced a dispute and who have accessed a fair formal, informal, alternative, or traditional dispute mechanism”; Second, “Percentage of total detainees who have been held in detention while awaiting sentencing or final disposition of their case.” The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) advocated significantly narrowing the scope of the first indicator, to be limited to victims of violence who reported the victimization to competent authorities. They argued that this approach would be more practical, because crime reporting rates can be measured using existing national data sources. For the second indicator, UNODC recommended modifying it to “unsentenced detainees as a percentage of overall prison population,” as this data could be reliably obtained from their existing systems covering 114 countries. [21]

Many organizations focused on SDG 16, including internal UN agencies, criticized UNODC’s proposals. They argued that excluding civil justice significantly narrowed the scope of the judicial remedies SDG 16.3 is meant to guarantee. Nevertheless, the more operationally feasible proposals from UNODC were ultimately adopted, largely because of its long-standing engagement in justice-related work, its established access to data channels, and its recognition by UN Security Council member states as an institutional expert on criminal justice.[22] In July 2017, the UN General Assembly adopted the global indicator framework for the SDGs. The indicators for SDG 16.3 were officially defined as follows: “16.3.1: Proportion of victims of violence in the previous 12 months who reported their victimization to competent authorities or other officially recognized conflict resolution mechanisms”; “16.3.2: Unsentenced detainees as a proportion of the overall prison population.”[23] These indicators sparked significant debate. In 2019, the IAEG-SDGs initiated a review of the indicator framework and issued a public call for feedback. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNDP, and the government of Germany each submitted recommendations regarding the indicators for SDG 16.3. Later, UNDP, together with UNODC and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), jointly submitted a draft proposal suggesting the addition of a new indicator that addresses broader legal problem resolution. In 2020, the UN Statistical Commission approved a third indicator for SDG 16.3: “16.3.3: Proportion of the population who have experienced a dispute in the past two years and who accessed a formal or informal dispute resolution mechanism, by type of mechanism.” This made SDG 16.3 one of the few targets within the sustainable development framework with three indicators.

The IAEG-SDGs published and updated metadata[24] for all three SDG 16.3 indicators, specifying the custodian agencies and monitoring requirements. UNODC serves as the custodian agency for all three indicators, with UNDP and OECD also serving as co-custodians for the third indicator. Custodian agencies play a key role in interpreting indicators and collecting data. Based on their input, the metadata provides detailed definitions and boundaries for the key terms used in each indicator. For example, “violence” in 16.3.1 includes physical, psychological, and sexual violence, with data required to be disaggregated by gender. The metadata also specifies the definition and scope of the three types of violence and the competent authorities. In 16.3.2, “detainees” refers to persons held in prison, penal, or correctional institutions for criminal reasons. In 16.3.3, “dispute” refers to “a justiciable problem” between individuals that may give rise to legal issues, covering a wide range of matters and extending beyond criminal matters. Dispute resolution mechanisms include all commonly used systems, not limited to traditional judicial bodies. The metadata also contains rationales for each indicator and explains how they relate to other indicators and targets. Regarding data collection methods, the metadata specifies the basis and sources of data, the timing of collection and publication, specific methods of collection and calculation, relevant departments and contact points, and guidance for national data submissions.

Through these indicators and their detailed metadata, we can better understand the meaning of “equal access to justice” under SDG 16.3 and clearly see the focus areas currently being monitored and promoted by the United Nations. With the addition of new indicators, access to justice under the sustainable development framework is no longer limited to the field of criminal justice. It has expanded to include civil and other areas. Nevertheless, indicators 16.3.1 and 16.3.3 mainly focus on the opportunity to access [conflict resolution] mechanisms, whereas 16.3.2 reflects only one aspect of criminal justice. These indicators do not address rights at various procedural stages or matters of compensation, nor state support measures such as legal aid—all of which are integral to “equal access to justice” under human rights treaties. This reveals a gap between the concept of “equal access to justice” as reflected in the current indicators and as defined in human rights treaties. However, it is also important to recognize that these indicators are designed for monitoring global progress and must take into account the feasibility of collecting data worldwide. Compared to economic targets, justice-related targets are more difficult to measure. Global monitoring requires substantial material resources and sources of authority, and countries vary in their capacity to collect and provide data. Imposing new legal obligations or requiring states to allocate more resources poses a challenge. The 2030 Agenda also emphasizes that “data and information from existing reporting mechanisms should be used where possible.” This shows that the differences in how the same right is defined under the two frameworks are closely tied to their monitoring mechanisms. The next section will compare the implementation mechanisms of the two frameworks to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how they promote access to justice.

III. Different Implementation Mechanisms and Monitoring Status

(1) Review Mechanisms under International Human Rights Treaties

Core international human rights treaties establish committees to monitor implementation, and the composition of these committees and their oversight mechanisms are clearly defined. Under the framework of human rights treaties, states parties are required to submit periodic reports to the committees on the implementation of such treaties. The committees convene sessions to review the reports and issue concluding observations. States then improve their implementation based on these observations and report back in the next review cycle. This section will not go into details of treaty body review mechanisms. Instead, it will use the 2023 review of China by the CEDAW Committee as an example to analyze how “access to justice” is reviewed under this mechanism.

In March 2020, China submitted its ninth periodic report to the CEDAW Committee, responding to the committee’s recommendations in its previous concluding observations about providing legal aid so that women can access effective legal protection. The report stated that the country had improved its legal aid and judicial assistance systems and “listed women as key targets of legal aid and included abuse, abandonment and domestic violence as additional matters for legal aid.”[25] The report illustrated its support for women’s access to legal aid by presenting data on the number of legal aid workstations and the number of women who had received legal aid services. Due to the global pandemic, the CEDAW committee did not hold its session to review China’s report until May 2023. Prior to the review, many civil society organizations submitted shadow reports to provide the committee with additional information on the country’s implementation, some of which highlighted the challenges women face within the justice system. During the review, civil society representatives had the opportunity to share their views either in person or online. Following the review, the committee issued its concluding observations, one section of which was devoted to “Women’s Access to Justice”. The committee acknowledged the progress made in the legal aid reform but noted that more disadvantaged groups of women continue to face barriers and intersecting forms of discrimination in accessing justice, including gender bias on the part of judicial personnel. Based on its General Recommendation No. 33 on access to justice, the committee made several recommendations to China[26], including providing gender equality training for the judiciary to raise awareness of women’s equal rights and eliminate gender bias in judicial proceedings, and offering legal aid and other judicial support to women who lack sufficient means—especially those facing intersectional discrimination. Although concluding observations do not carry the same binding force as domestic laws or court judgments, the review is not a one-time deal. The committee requires states parties to respond to inquiries and report to the committee periodically, which to some extent pushes governments to bring domestic laws more closely in line with international standards. The observations also provide a foundation and framework for civil society advocacy. Notably, this round of concluding observations included a section specifically addressing the importance of gender equality in the Sustainable Development Agenda. It urged the Chinese government to recognize women as active drivers of sustainable development and to take action to support them in fulfilling this role.

Each human rights treaty is reviewed individually and focuses on the specific group it aims to protect. However, every human rights treaty is an integral part of the broader UN human rights system, and there are overlaps and intersections between them. To enhance the effectiveness of the treaty system, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has made efforts to adopt a systematic approach to monitoring human rights implementation. This includes coordinating the work of the treaty bodies and aligning with other UN human rights mechanisms to promote the comprehensive fulfillment of obligations by States.[27] Another important human rights mechanism is the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), established under the United Nations Human Rights Council. This mechanism conducts comprehensive peer reviews of the human rights situation in each country, with other UN member states providing recommendations to the state under review. In 2024, China underwent its UPR and received 428 recommendations from other countries, of which it accepted 290. According to OHCHR statistics, 44% of these recommendations were related to SDG 16, and about ten specifically addressed access to justice, including issues of procedure and legal support. China indicated its acceptance of all of these recommendations.[28]

The monitoring mechanisms of the various human rights treaties are generally similar. They assess the status of each state party based on the legal framework of the respective treaty, and participation is premised on the state’s ratification, meaning the obligations are not universally binding, and there are no uniform indicators for measurement. While treaty bodies are highly professional, the review processes are often time-consuming and carry a heavy workload. Most are unable to review states parties within the intended cycles (usually every four to five years). For example, the intervals between the three most recent CEDAW Committee reviews of China have each exceeded eight years. In contrast, the monitoring of the SDGs is more frequent, though the scope and mechanisms differ significantly.

(2) Monitoring Mechanism under the Sustainable Development Framework

The 2030 Agenda outlines how the SDGs should be implemented and monitored, including the principles of implementation, the development of indicators, and the arrangements for tracking and evaluation. It calls on member states to treat the goals as an indivisible whole and to act in accordance with international human rights treaties and other international laws. It also calls on them to fulfill their obligations under international law. The agenda emphasizes the leading role of states in assessments and supports the establishment of a global indicator framework. The High-Level Political Forum serves as the primary platform for evaluating national performance and global trends. It also stresses the importance of regional cooperation and encourages stakeholders to contribute to advancing the sustainable development agenda. The following section will analyze how this mechanism functions using domestic and global monitoring of SDG 16.3 as a case study.

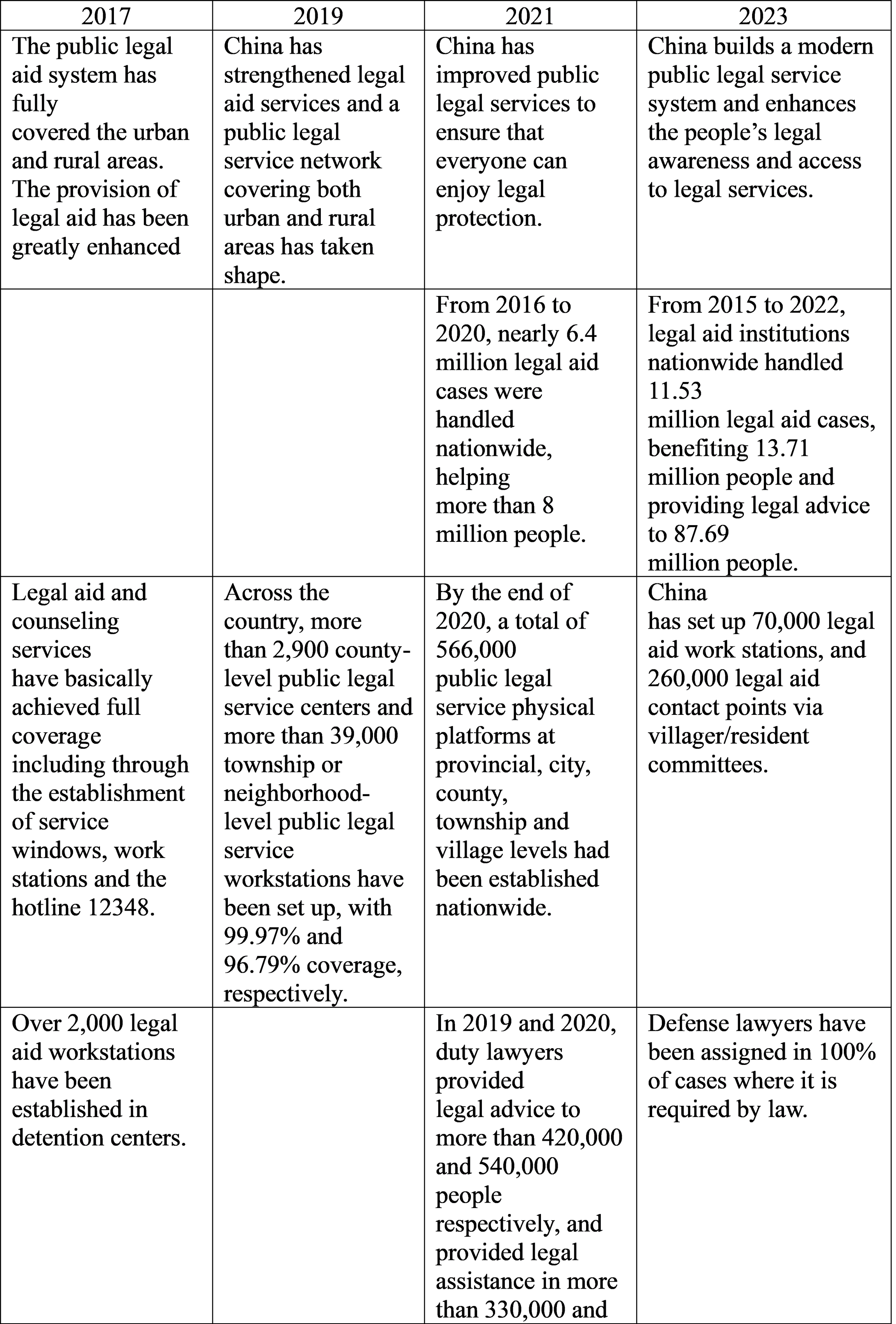

National-level assessments lay the groundwork for global evaluation. According to the 2030 Agenda, each country may develop its own national sustainable development implementation plan based on its specific context, define its own priorities and conduct periodic reviews. In September 2016, China released the National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes implementation measures for achieving all 169 specific targets. For SDG 16.3, the National Plan outlines the following actions: “Deepen judicial reforms to establish a judicial system that is just, effective, and authoritative. Improve the judicial protection of rights and the judicial supervision over government power. Improve judicial division of labor and checks and balances. Improve the rule of law in terms of social governance. Establish a public legal service system that covers both urban and rural areas. Improve the legal aid system and judicial relief system.”[29] This entry covers a wide range of areas. The first part focuses on judicial system reform and emphasizes the judicial protection of rights; the latter addresses the construction of public legal services, with an emphasis on urban-rural coverage. However, the National Plan does not establish measurable indicators, nor does it respond directly to the three global indicators set under the SDG 16.3 framework. To date, China has published four progress reports on the implementation of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Although each report covered all 17 goals, the reports did not directly address specific targets under each goal. The section on SDG 16 includes content related to access to justice, such as the development of legal aid laws, the construction of the legal service system, and legal awareness campaigns. A comparison of the data presented in the four progress reports (see Table 1 below) shows a gradual increase in data categories, including figures on legal aid cases, legal consultations, and legal aid recipients. Unfortunately, the data presentation and statistical standards vary across the four reports, making it difficult to trace year-on-year trends. Moreover, the reports lack comparisons between the legal services people received and their actual legal needs. For example, they do not show the proportion of people who received legal aid out of those who sought it. This makes it difficult to accurately interpret the significance of the data.

Table 1: A Comparison of Selected Content from China’s Four Sustainable Development Progress Reports

Source: China’s Progress Report on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2017, 2019, 2021, 2023, available at https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/zt_674979/dnzt_674981/qtzt/2030kcxfzyc_686343/zw/, last accessed on October 31, 2024.

In addition to publishing progress reports, countries independently decide whether to participate in Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs), which are conducted at the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) held annually by the United Nations. The UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) provides guidance to countries participating in VNRs, encouraging them to report on their overall progress toward the SDGs and to provide in-depth reporting on the goals they select as their priorities. Prior to the HLPF, regional commissions (in Asia, it is ESCAP) organize meetings to discuss regional issues and provide a platform for countries participating in VNRs to share their experiences. After submitting their VNR reports, countries present them at the HLPF, where other member states and stakeholders can pose questions on site.[30] The VNR process does not involve a committee to review national implementation, unlike human rights treaty reviews. Instead, its format more closely resembles that of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), functioning as a peer exchange of experiences among member states. Following the national presentation, there is no formal procedure for collecting recommendations from other states, as in the UPR, nor does it produce concluding observations comparable to those issued by treaty bodies. The process mainly relies on states to summarize their own experiences and take follow-up actions. China has participated in the VNR process twice, in 2016 and 2021. The VNR submitted in 2021 was shorter than the progress reports and did not address issues of access to judicial remedies.[31]

According to the 2030 Agenda, the HLPF plays a central role in overseeing and evaluating the implementation of the SDGs. As an intergovernmental mechanism, the HLPF holds meetings under two formats: high-level meetings are held under the UN General Assembly every four years,[32] and annual meetings are held under the auspices of the ECOSOC during its substantive session.[33] In addition to VNRs, the HLPF conducts thematic reviews of selected goals each year and publishes an annual report based on data monitored under the global indicator framework, outlining global progress trends toward the SDGs. The 2024 annual report[34] shows that among the 169 specific targets, nearly half are showing minimal or moderate progress, and progress on over a third has stalled or even regressed. SDG 16.3 is reported to be in a state of stagnation. The report includes two sets of data related to SDG 16.3. One set corresponds to Indicator 16.3.1, which concerns reporting crimes to competent authorities. Data from 53 countries covers three types of violent acts: physical assault, robbery, and sexual assault. Reporting rates for the first two (36% and 45%) are significantly higher than for sexual assault (17%). The other set corresponds to Indicator 16.3.2, the proportion of unsentenced detainees, which remained around 30% between 2015 and 2022. These data are collected by the custodian agencies mentioned earlier, according to their respective roles and data channels, and are submitted to the UN Statistics Division for inclusion in official reports only after approval by member states. As previously mentioned, custodian agencies provide guidance for national data collection through the metadata for each indicator. For Indicator 16.3.3 specifically, the three custodian agencies have developed dedicated operational manuals to support national data collection, transforming measurement methods into a set of survey questions that countries can use. However, to date, the extended SDG 16 report published by the custodian agencies still does not include data on 16.3.3. [35] The OECD analyzed limited data received from only six countries or territories in a policy paper aimed at improving monitoring of 16.3.3.[36] This data scale is clearly insufficient to reflect global trends or to monitor the status of SDG 16.3 in the field of civil justice.

The lack of data has become a major challenge in assessing progress toward this goal. In 2024, the HLPF conducted a thematic review of SDG 16. The expert group meeting focused heavily on data issues and called for a “data revolution.” Experts emphasized the importance of integrating multiple data sources for monitoring SDG 16. Non-official data can supplement information that official sources fail to capture. Examples include the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index[37] and reports released by coalitions focusing on SDG 16.[38] The meeting recommended that data collection be more inclusive and involve contributions of stakeholders. Civil society organizations representing different groups play an essential role in accessing and producing such data.[39] This aligns with the principles outlined in the 2030 Agenda, which states that evaluations should be open, inclusive, participatory, and transparent, and supportive of reporting by diverse stakeholders.

Although VNRs do not have a formal channel for civil society to submit shadow reports as they may during human rights treaty reviews, there are both formal and informal avenues for civil society participation. The 2030 Agenda explicitly incorporates multi-stakeholder collaboration into Targets 17.6 and 17.7 and calls for an annual multi-stakeholder forum. The UN General Assembly has also passed resolutions recognizing 21 Major Groups and other Stakeholders (MGoS) and ensuring their full participation in the HLPF, including attending all formal sessions, submitting documents, making oral statements during VNR sessions, and organizing side events in cooperation with member states and the UN Secretariat during the HLPF.[40] The MGoS Coordination Mechanism plays a key role in enabling civil society to effectively engage in the Sustainable Development Agenda. Although there is no MGoS group dedicated solely to SDG 16.3, access to justice is a relevant cross-cutting issue for every group. Organizations focused on the rule of law and human rights pay particular attention to SDG 16 and have formed many platforms, networks, and alliances in support of SDG16, such as Pathfinders,[41] the SDG 16 Hub,[42] #SDG16Now,[43] and the TAP Network.[44] These groups collaborate on numerous initiatives to promote the implementation and evaluation of relevant targets. These initiatives include publishing reports and declarations. For example, the “Rome Civil Society Declaration on SDG 16” has been issued annually for the past five years.[45] Each year’s declaration summarizes challenges facing this goal and puts forward a series of recommendations.

From national reporting to global evaluation to multi-stakeholder engagement, we observe that the SDG monitoring mechanism differs significantly from that of human rights frameworks. However, the two also share commonalities, such as an emphasis on marginalized groups and the importance of civil society participation. What emerges is a powerful model for visualizing global trends through a unified set of indicators and for channeling attention from diverse stakeholders. At the same time, the monitoring of SDG 16.3, a goal related to justice, reveals the difficulty of using quantitative indicators within a development framework. Custodian agencies face challenges in data collection, and relying solely on existing data is not sufficient for fully assessing the state of “equal access to justice.” This is not just a matter of a data gap that prevents us from covering enough countries, but a structural limitation of using quantitative metrics to evaluate a justice goal. These shortcomings require the support of complementary mechanisms.

4. Advancing Justice through the Synergy of Development and Human Rights

In response to the lack of attention to human rights and the rule of law in development frameworks, the 2030 Agenda is rooted in human rights treaties and has integrated fundamental human rights into many of its goals. Equal access to justice is a prime example of a key intersection between development and human rights. Yet, the notion of justice differs across the two frameworks. Human rights conventions cover a wide spectrum of rights throughout all stages of judicial processes, including criminal, civil, and other areas. In contrast, the 2030 Agenda primarily focuses on access to judicial mechanisms. While the indicators have expanded from criminal justice to include civil justice, they still fall short of the multi-dimensional scope covered by human rights treaties. The monitoring mechanisms of the two frameworks also differ. In one case, expert committees conduct periodic reviews based on legally binding treaty obligations and issue targeted recommendations such as how to improve access to justice for specific groups. In the other, VNRs focus on peer exchange among countries, and the HLPF-issued annual reports do not disclose country-specific data. The HLPF report shows that SDG 16.3 is in a state of stagnation and calls for urgent action, but it does not offer concrete recommendations. Furthermore, the lack of data related to SDG 16.3 makes measuring progress in the justice domain highly challenging.

Despite the gap between the 2030 Agenda’s approach to justice and the more robust standards found in human rights treaties, the 2030 Agenda has strengths that complement and reinforce human rights mechanisms. For one thing, the 2030 Agenda represents the broadest political consensus among states, and reflects collective political will. Its integration into development frameworks lends weight to judicial justice as a developmental imperative. This helps states recognize the value of justice in promoting social and economic development, which in turn could drive the implementation of human rights and collective progress. In addition, as a global priority of the United Nations, the 2030 Agenda influences other international mechanisms. Treaty bodies now reference SDG goals in their concluding observations, and UPR recommendations are categorized by corresponding SDGs. The ongoing 30-year review[46] of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on gender equality also emphasizes alignment with 2030 Agenda mechanisms, aiming to “promote consistency and comparability between reports of different countries.”[47] Although data collection challenges persist, establishing a global indicator framework provides a platform for broad stakeholder engagement. Regarding access to justice specifically, a variety of organizations and networks are leveraging SDG 16 as a foundation for carrying out assessments and monitoring activities. These efforts increasingly incorporate other human rights standards to enrich the understanding of judicial justice and address the limitations of existing indicators and gaps in official data.

The 2030 Agenda offers a new pathway for advancing both global development and human rights. However, for this mechanism to fully realize its potential, especially in promoting equal access to justice for marginalized groups, it must operate in synergy with existing human rights frameworks. A 2019 report on judicial justice highlighted that roughly two-thirds of the global population still lacks meaningful access to justice, and women, children, persons with disabilities, and other vulnerable groups are among those most affected.[48] Building on SDG 16.3’s vision of “Justice for All,” the report calls for a shift from a model that provides justice only for the few, to one that delivers measurable improvements in justice for all. It also emphasizes the need to construct people-centered justice systems. Accordingly, national-level evaluations of SDG 16.3 should delve deeper into people’s actual justice needs, understanding how different groups experience fairness or discrimination, and identify the structural barriers and unmet needs faced by marginalized communities. In this regard, human rights treaties that focus on specific vulnerable groups could offer valuable guidance. These frameworks propose detailed measures to ensure access to judicial remedies and consistently emphasize the critical role of legal aid in achieving equal access to justice. Vulnerable individuals often face considerable disadvantages in asserting their rights, especially when pitted against more resourceful adversaries. They typically lack the resources and opportunities to access professional legal support. Therefore, legal aid systems are essential measures that states must adopt to fulfill the right to judicial redress and uphold justice. Taking the example of the barriers women face in accessing justice, the CEDAW committee has urged states parties to establish accessible, sustainable legal aid systems that are responsive to women’s needs. It also offers concrete recommendations related to the types of procedures covered, the kinds and quality of services offered, and how women can learn about and access these services, thus providing a roadmap for effective legal aid frameworks.[49]

At the core of SDG 16.3 is the imperative to “ensure equal access to justice for all,” in response to widespread global deficiency of judicial protection. However, setting goals and monitoring indicators alone is not enough to close the real gaps in access to justice. Achieving this ambition requires active integration with human rights mechanisms and inclusive engagement from diverse stakeholders. States must consider the resource limitations and structural barriers faced by vulnerable groups and respond by designing robust systems, such as legal aid, to build a people-centered justice framework. This means much more than improving an individual’s opportunity to access dispute resolution mechanisms. It also means ensuring that the legal and judicial outcomes are just and equitable.[50]

***

This article was originally published in the Anti-Discrimination Law Review [反歧视评论], No. 12, 2025 under the title 所有人的正义:以发展和人权测量司法保护, and translated into English by the U.S.-Asia Law Institute. The institute thanks the author and publisher for permission to publish it in English.

** Huang Yizhi is a PhD candidate and an assistant research officer at the Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong. Her research focuses on legal policy and advocacy for the rights of specific populations.

[1] United Nations General Assembly: Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1, 2015.

[2] OHCHR, The Core International Human Rights Treaties, United Nations Publication, 2006.

[3] These documents include the 1987 report Our Common Future, the 1992 Agenda 21, and the 2000 Millennium Development Goals, among others.

[4] UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda (UNSTT), Realizing the Future We Want for All: Report to the Secretary-General, 2012, https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Post_2015_UNTTreport.pdf, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[5] Saferworld, From the Sustainable Development Goals to the post-2015 development agenda: building a consensus for peace, 2014, https://www.saferworld-global.org/resources/publications/831-from-the-sustainable-development-goals-to-the-post-2015-development-agenda-building-a-consensus-for-peace, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[6] Marcel Smits, David Connolly and Peter van Sluijs, Making SDG 16.3 Work for the Rule of Law and Access to Justice: Measuring Progress in Fragile and Conflict-affected States 14 December 2017, https://www.cspps.org/news/making-sdg-163-work-rule-law-and-access-justice-measuring-progress-fragile-and-conflict, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[7] Sarah Hearn, How to Achieve Sustainable Peace: The Radical Potential of Implementing UN Sustainable Development Goal 16, 2016, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/12657.pdf, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[8] United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 7: “All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.”

[9] United Nations, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, art. 26: “All persons are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection of the law.”

[10] Mauro Cappelletti (Ed.). Access to Justice and the Welfare State, Trans. Liu Junxiang et al. Beijing: Law Press, 2000, pp. 1–23. (Originally in Italian)

[11] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Access to Justice Practice Note, 2004.

https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/Justice_PN_En.pdf (Accessed 31 Oct 2024)

[12] CEDAW. General Recommendation No. 33 on Women’s Access to Justice, CEDAW/C/GC/33, 2015.

[13] In this section, the author uses the Chinese translation “获得司法保护” that is used in official versions of the human rights treaties.

[14] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006), Article 13 (1).

[15] CERD, General Recommendation No. 31 on the Prevention of Racial Discrimination in the Administration and Functioning of the Criminal Justice System, CERD/C/GC/31, 2005.

[16] CRPD, General Comment No. 1 – Article 12: Equal Recognition Before the Law, CRPD/C/GC/1, 2014.

[17] CEDAW, General Recommendation No. 33 on Women’s Access to Justice, CEDAW/C/GC/33, 2015.

[18] CRC, General Comment No. 24 on Children’s Rights in the Child Justice System, CRC/C/GC/24, 2019.

[19] In this section, the author uses the Chinese translation “诉诸司法” that is used in official versions of the 2030 Agenda.

[20] The working group is composed of representatives from national statistical offices of 28 member states, with regional and international organizations participating as observers. It is responsible for developing a specific indicator framework for the global monitoring of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As the representative for the East Asian region, the National Bureau of Statistics of China participated in the development of the global indicator framework through the expert group.

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/ (last accessed: October 31, 2024)

[21] Margaret Satterthwaite and Sukti Dhital, Measuring Access to Justice: Transformation and Technicality in SDG 16.3, Global Policy, Vol. 10, No. 1 (2019), p. 98.

[22] Margaret Satterthwaite and Sukti Dhital, Measuring Access to Justice: Transformation and Technicality in SDG 16.3, Global Policy, Vol. 10, No.1 (2019), p. 98.

[23] UNGA, 71/313. Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/71/313, 2017.

[24] SDG Indicators Metadata Repository, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata (last accessed: October 31, 2024).

[25] CEDAW, Ninth Periodic Report Submitted by China under Article 18 of the Convention, CEDAW/C/CHN/9, 2020.

[26] CEDAW, Concluding Observations on the Ninth Periodic Report of China, CEDAW/C/CHN/CO/9, 2023.

[27] The OHCHR is the leading UN entity in the field of human rights, and its work is linked to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://www.ohchr.org/zh/sdgs (last accessed: October 31, 2024).

[28] OHCHR, Thematic List of Recommendations and Infographic for UPR of China (4th Cycle - 45th Session), 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr/cn-index, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[29] China’s National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, September 2016. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-10/13/5118514/files/4e6d1fe6be1942c5b7c116e317d5b6a9.pdf (last accessed: October 31, 2024).

[30] Each country is allocated 20 to 30 minutes—30 minutes for first-time participants and 20 minutes for returning participants. The time is divided equally between the national presentation and the question-and-answer session.

[31] China’s Voluntary National Review Report on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 2021. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/zt_674979/dnzt_674981/qtzt/2030kcxfzyc_686343/zw/202107/P020210912807817369012.pdf (last accessed: October 31, 2024).

[32] High-level meetings are attended by heads of state and government, and the president of the General Assembly serves as chair. The two-day session results in a brief political declaration that is submitted to the General Assembly.

[33] The annual meetings include five days of senior official meetings and three days of ministerial meetings. At the conclusion, a ministerial declaration is adopted and included in the ECOSOC report to the General Assembly.

[34] UNGA, Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Report of the Secretary-General, A/79/79–E/2024/54, 2024.

[35] UNSD, The Sustainable Development Goals Extended Report 2024 for SDG 16, 2024, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/extended-report/Extended-Report_Goal-16.pdf, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[36] OECD and New York University, Improving the Monitoring of SDG 16.3.3, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/09/improving-the-monitoring-of-sdg-16-3-3_ba6098ca/c5fbed7e-en.pdf, accessed October 31, 2024.

[37] The World Justice Project (WJP) is an independent, multidisciplinary organization working to create knowledge, build awareness, and stimulate action to advance the rule of law worldwide. It released the 2024 WJP Rule of Law Index. https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/ (last accessed: October 31, 2024).

[38] TAP Network, Halfway to 2030 Report on SDG 16+, 2023. https://www.sdg16now.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Halfway-to-2030-Report-Digital.pdf, accessed October 31, 2024.

[39] HLPF, Thematic Review Expert Group Meeting Summary for Session on SDG 16, 2024. https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/HLPF%202024_SDG%2016%20EGM%20Summary_FINAL_0.pdf, accessed October 31, 2024.

[40] UNGA, 67/290. Format and organizational aspects of the high-level political forum on sustainable development, A/RES/67/290, 2013.

[41] Pathfinders is a cross-regional and member state-led, multi-stakeholder coalition committed to advancing action on peace, justice, equality and inclusive institutions through the Sustainable Development Goals and beyond (SDG16+). https://www.sdg16.plus/about/, last accessed: October 31, 2024.

[42] The SDG 16 Hub is a platform for practitioners that responds to the increasing demand for a space for knowledge sharing and collaboration on SDG 16 and to ensure meaningful and impactful exchanges. It aims to bring together all stakeholders interested in SDG 16 to share experiences related to its key pillars. https://www.sparkblue.org/SDG16Hub#,last accessed: October 31, 2024.

[43] #SDG16Now is a global civil society campaign to support accelerated action towards SDG16+ around peaceful, just and inclusive societies. https://sdg16now.org/, last accessed: October 31, 2024.

[44] The Transparency, Accountability, and Participation Network (TAP Network) is a broad international coalition of civil society organizations (CSOs) working together to advance SDG 16+ by promoting peace, justice, and inclusive societies, and to help enhance accountability for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). https://tapnetwork2030.org/about/, last accessed: October 31, 2024.

[45] 2024 Rome Civil Society Declaration on SDG 16, https://www.cspps.org/publications/2024-rome-civil-society-declaration-sdg-16, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[46] In 2025, the international community will celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995). In March 2025, the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women will review and assess the progress in implementing the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and accelerate efforts to achieve gender equality and empower women and girls.

[47] UN Women, Guidance Note for Comprehensive National-level Reviews for Thirtieth Anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and Adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995), 2023, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/beijing30_guidance_note_en.pdf, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[48] Initiated by Pathfinders, drawing on research by the world’s leading justice organizations and experts, this report provides a first estimate of the global justice gap https://www.sdg16.plus/resources/justice-for-all-report-from-the-task-force-on-justice-overview/, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

[49] CEDAW, General Recommendation No. 33 on Women’s Access to Justice, CEDAW/C/GC/33, 2015.

[50] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Access to Justice Practice Note, 2004, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/Justice_PN_En.pdf, accessed 31 Oct 2024.

Suggested citation:

Yizhi Huang, “Justice for All: Measuring Access to Justice Under the Development and Human Rights Frameworks,” USALI East-West Studies, 4, No. 1, February 8, 2026, https://usali.org/publications/measuring-access-to-justice-in-the-contexts-of-development-and-human-rights.

The views expressed here are those of the author, and do not represent those of USALI or NYU.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.